From suburbia and skyscraper scrawl to the open prairies and 'local color', slum life to rural idyll: reprinting American and British literary classics.

Articles / Essays

Articles and essays on anything bookish or of literary matters

Articles and essays on anything bookish or of literary matters

Some articles have appeared before as blog posts on the Albion Beatnik Bookstore website. The bookshop closed in January 2018. Articles from guest contributors are welcomed.

Barbara Pym: It’s The Church Pew That Moves, Not The Earth

You have to be bonkers not to love Barbara Pym’s novels. Her acme was a 1950s suburban or neo-rural setting where The Archers doesn’t quite meet James Bond, because you don’t get the offstage milking of cows, and if the tea is stirred, well it’s never shaken. The stories thrive off crinoline and a matching cruet set, cups of tea always, gallons of the stuff, but also sheer delight. They offer welcome shelter from today’s boorish age: the best bookshops lay out her books as though pots of jam on display at the local church fete…

You have to be bonkers not to love Barbara Pym’s novels. Her acme was a 1950s suburban or neo-rural setting where The Archers doesn’t quite meet James Bond, because you don’t get the offstage milking of cows, and if the tea is stirred, well it’s never shaken. The stories thrive off crinoline and a matching cruet set, cups of tea always, gallons of the stuff, but also sheer delight. They offer welcome shelter from today’s boorish age: the best bookshops lay out her books as though pots of jam on display at the local church fete…

Agatha Christie, Sucking Mintoes in the Bath with

Murder On The Orient Express has one of the classic whodunit endings. The book was published first as a serialisation in 1933 in the United States, and this gets to the storyboard stuffing of Christie: polite chunks of rehearsed action left on a refined cliffhanger, gentle as she goes. There is never any sense that she put herself our for her writing or suffered for her art, and she might have found it difficult to sparkle today in our blithe cut and paste, copy-thy-neighbour world. She borrowed from what was to hand always, so her characters are often stereotypical and her plots are laboriously unadventurous. Probably Christie put more effort and imagination into drafting the articles of association of Agatha Christie Ltd and tax avoidance than her writing…

Murder On The Orient Express has one of the classic whodunit endings. The book was published first as a serialisation in 1933 in the United States, and this gets to the storyboard stuffing of Christie: polite chunks of rehearsed action left on a refined cliffhanger, gentle as she goes. There is never any sense that she put herself our for her writing or suffered for her art, and she might have found it difficult to sparkle today in our blithe cut and paste, copy-thy-neighbour world. She borrowed from what was to hand always, so her characters are often stereotypical and her plots are laboriously unadventurous. Probably Christie put more effort and imagination into drafting the articles of association of Agatha Christie Ltd and tax avoidance than her writing…

NATHANAEL WEST: “WEST’S DISEASE” & THE AMERICAN DREAM

Although Nathanael West’s books did not sell well in his lifetime, the influence of his Expressionist black satire was far-reaching. West was deeply disappointed by the American Dream, and his novels read still as bleak and unremittingly dark, apolitical, and as dismissal of faith, artistic expression and romantic love. He has become a masthead for subsequent and similar dissent. W. H. Auden in 1962 coined the phrase “West’s Disease,” and wrote that these books were “parables about a Kingdom of Hell whose ruler is not so much a Father of Lies as a Father of Wishes.”

Although Nathanael West’s books did not sell well in his lifetime, the influence of his Expressionist black satire was far-reaching. West was deeply disappointed by the American Dream, and his novels read still as bleak and unremittingly dark, apolitical, and as dismissal of faith, artistic expression and romantic love. He has become a masthead for subsequent and similar dissent. W. H. Auden in 1962 coined the phrase “West’s Disease,” and wrote that these books were “parables about a Kingdom of Hell whose ruler is not so much a Father of Lies as a Father of Wishes.”

JULIAN MACLAREN-ROSS: SQUANDERED DAYLIGHT, NEON-MOONLIGHT

Julian MacLaren-Ross (1912-1964) delineated with brilliance and acuity the sleazy bohemian atmosphere of post-war Soho through a series of amusing short stories and eight novels. His writing style is lively, vernacular, even Americanized – think Scott Fitzgerald, maybe even Hunter S. Thompson. He made his mark with the opening line of a short story he wrote for Cyril Connolly’s Horizon in 1940, ‘A Bit of a Smash in Madras’. “Absolute fact, I knew fuck-all about it:” this as well as other lines had to be smoothed over by Stephen Spender, the piece as a whole as relentless in its insight as it is forthright, and powerfully persuasive… Had he come of age with the Angry Young Men his stature today would be more assured…

Julian MacLaren-Ross (1912-1964) delineated with brilliance and acuity the sleazy bohemian atmosphere of post-war Soho through a series of amusing short stories and eight novels. His writing style is lively, vernacular, even Americanized – think Scott Fitzgerald, maybe even Hunter S. Thompson. He made his mark with the opening line of a short story he wrote for Cyril Connolly’s Horizon in 1940, ‘A Bit of a Smash in Madras’. “Absolute fact, I knew fuck-all about it:” this as well as other lines had to be smoothed over by Stephen Spender, the piece as a whole as relentless in its insight as it is forthright, and powerfully persuasive… Had he come of age with the Angry Young Men his stature today would be more assured…

Dornford Yates: Snobbery with Violence

These books are for blokes who never grew up, but are somewhat charming in their innocence and aspiration, at least when pitted against their modern day equivalents – Jack Reacher or Jason Bourne, neither of whom could be described thus: it “was not Mansel’s way to shoot a man in the back.” Yates was a kindred spirit with Sapper and John Buchan – gloriously referred to by Alan Bennett as the “Snobbery with Violence” school of writing, that “runs like a thread of good tweed through twentieth century literature.” The books are ignorant of the law and its procedure, its heroes are bereft of any contact with official lawmen, customs’ control is an irrelevance (it would be an inconvenience if otherwise), but the motivation of the main characters in the stories is fun rather than duty. Richard Chandos (who has been sent down from Oxford for “beating up some Communists”) with his two sidekicks Hanbury and Mansel stampede across continental Europe heading big time criminals off at the pass, protecting innocent lives, chatting up high class floosies, and perhaps amassing a small fortune in treasure along the way (it’ll be the usual treasure described in the ‘Famous Five’ books by Enid Blyton, the filigree of each story is quite childish)…

These books are for blokes who never grew up, but are somewhat charming in their innocence and aspiration, at least when pitted against their modern day equivalents – Jack Reacher or Jason Bourne, neither of whom could be described thus: it “was not Mansel’s way to shoot a man in the back.” Yates was a kindred spirit with Sapper and John Buchan – gloriously referred to by Alan Bennett as the “Snobbery with Violence” school of writing, that “runs like a thread of good tweed through twentieth century literature.” The books are ignorant of the law and its procedure, its heroes are bereft of any contact with official lawmen, customs’ control is an irrelevance (it would be an inconvenience if otherwise), but the motivation of the main characters in the stories is fun rather than duty. Richard Chandos (who has been sent down from Oxford for “beating up some Communists”) with his two sidekicks Hanbury and Mansel stampede across continental Europe heading big time criminals off at the pass, protecting innocent lives, chatting up high class floosies, and perhaps amassing a small fortune in treasure along the way (it’ll be the usual treasure described in the ‘Famous Five’ books by Enid Blyton, the filigree of each story is quite childish)…

EDMUND CRISPIN: THE AWKWARD HOUR BETWEEN EVENSONG & COCKTAILS

Edmund Crispin’s The Moving Toyshop is one of the classic Oxford novels. Crispin was the pseudonym of Robert Bruce Montgomery, a composer of vocal and choral music which included An Oxford Requiem (1951). Hindered by a lack of musical self-belief, he found it easier to turn his hand to film work and pocket money; he wrote the scores for many British comedies of the 1950s (including the first Carry On films – for which he should have been shot). Crispin wrote short stories and nine detective novels which featured Gervase Fen, a Professor of English at the University and a fellow of the fictional St. Christopher’s College, housed next to St. John’s College, Crispin’s alma mater…

Edmund Crispin’s The Moving Toyshop is one of the classic Oxford novels. Crispin was the pseudonym of Robert Bruce Montgomery, a composer of vocal and choral music which included An Oxford Requiem (1951). Hindered by a lack of musical self-belief, he found it easier to turn his hand to film work and pocket money; he wrote the scores for many British comedies of the 1950s (including the first Carry On films – for which he should have been shot). Crispin wrote short stories and nine detective novels which featured Gervase Fen, a Professor of English at the University and a fellow of the fictional St. Christopher’s College, housed next to St. John’s College, Crispin’s alma mater…

Ion Sirbu & The Small, Bearded Priest

During his lifetime Sirbu achieved no commercial success and little favourable review, though he was a quiet hero, literary and otherwise, to many. He saw his days out as a theatre administrator in Craiova and died just a few months before the Revolution of 1989. His writing found a Romanian audience in the heady cultural times after then, and he was translated elsewhere in Eastern Europe but never in Britain. A great deal of Sirbu’s writing was destroyed by the state police, only some of what was taken from him did he manage to redraft. Apart from his theatre work, only four novels (including two for children) survive. His most impressive book is Adio, Europa!, an allegorical novel not dissimilar to The Master & Margarita; like Bulgakov’s novel, it was published posthumously. ..

During his lifetime Sirbu achieved no commercial success and little favourable review, though he was a quiet hero, literary and otherwise, to many. He saw his days out as a theatre administrator in Craiova and died just a few months before the Revolution of 1989. His writing found a Romanian audience in the heady cultural times after then, and he was translated elsewhere in Eastern Europe but never in Britain. A great deal of Sirbu’s writing was destroyed by the state police, only some of what was taken from him did he manage to redraft. Apart from his theatre work, only four novels (including two for children) survive. His most impressive book is Adio, Europa!, an allegorical novel not dissimilar to The Master & Margarita; like Bulgakov’s novel, it was published posthumously. ..

Heathcote Williams: The Local Polemic

But for all of that, his polemic voice came as a birthright: the polemic, like satire, is the last refuge of the privileged. “Poetry is heightened language,” he said a few years ago, “and language exists to effect change, not to be a tranquilizer.” I’m not so sure about the consistency of that. Marx, for one, made a bad poet. And if the privileged do either polemic or satire (the middle class do sitcom), it is only the working class who do revolution. Heathcote never did revolution, he did reportage… He wrote once of Shelley as an outsider, as a traitor to his class, too. But that’s not the stuff of revolution. Perhaps that observation of Shelley was autobiographical displacement…

But for all of that, his polemic voice came as a birthright: the polemic, like satire, is the last refuge of the privileged. “Poetry is heightened language,” he said a few years ago, “and language exists to effect change, not to be a tranquilizer.” I’m not so sure about the consistency of that. Marx, for one, made a bad poet. And if the privileged do either polemic or satire (the middle class do sitcom), it is only the working class who do revolution. Heathcote never did revolution, he did reportage… He wrote once of Shelley as an outsider, as a traitor to his class, too. But that’s not the stuff of revolution. Perhaps that observation of Shelley was autobiographical displacement…

MALCOLM SAVILLE’S YARD BROOM

Malcolm Saville was born in Hastings in 1901 and educated there. His first job was as a clerk with the Oxford University Press, and the rest of his working life was spent in publishing. At various times he edited journals (My Garden magazine in the late 1940s, Sunny Stories in the late 1950s). He was a devout Christian, and this aspect to his life found its way on to the written page; his lifetime passions are redolent of the childhood interests of his time – rambling, natural history and cricket; he is the personification of wholesomeness – outdoor pursuit, bike rides, puncture kits, camp fires, fizzy pop if a good boy, crisps with a separate twist of salt in the packet, Sunday school table tennis, hobbies and respect for elders and betters. He was an ornamental one-nation Conservative by instinct and like so many of his generation he dusted his political views as though they were trinkets on a sideboard…

Malcolm Saville was born in Hastings in 1901 and educated there. His first job was as a clerk with the Oxford University Press, and the rest of his working life was spent in publishing. At various times he edited journals (My Garden magazine in the late 1940s, Sunny Stories in the late 1950s). He was a devout Christian, and this aspect to his life found its way on to the written page; his lifetime passions are redolent of the childhood interests of his time – rambling, natural history and cricket; he is the personification of wholesomeness – outdoor pursuit, bike rides, puncture kits, camp fires, fizzy pop if a good boy, crisps with a separate twist of salt in the packet, Sunday school table tennis, hobbies and respect for elders and betters. He was an ornamental one-nation Conservative by instinct and like so many of his generation he dusted his political views as though they were trinkets on a sideboard…

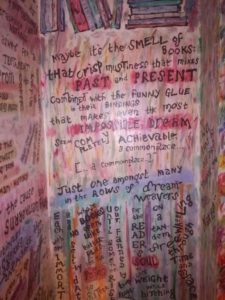

Sally Bayley: Girl With Dove

I have read recently Girl With Dove: A Life Built By Books by Sally Bayley, a childhood autobiography. Waterstone’s marketing tag for the book is that it is a “very eccentric memoir.” It might be eccentric in that it touches the eccentricities of childhood, but more likely it is very playful, certainly very different. Playful because it has been written with a sense of danger and very much composed on the hoof; there can be no blueprint for a book like this, for it has followed instinct rather than form or structure. And it is different to other memoir because its obfusc and scant narrative hovers in our sight, and as readers we can try to steady ourselves with it along the way; yet beneath a palimpsest of childhood enchantment is revealed. This is a book that has been pruned to its essentials, rather like Sally’s mother prunes her rose garden throughout the book…

I have read recently Girl With Dove: A Life Built By Books by Sally Bayley, a childhood autobiography. Waterstone’s marketing tag for the book is that it is a “very eccentric memoir.” It might be eccentric in that it touches the eccentricities of childhood, but more likely it is very playful, certainly very different. Playful because it has been written with a sense of danger and very much composed on the hoof; there can be no blueprint for a book like this, for it has followed instinct rather than form or structure. And it is different to other memoir because its obfusc and scant narrative hovers in our sight, and as readers we can try to steady ourselves with it along the way; yet beneath a palimpsest of childhood enchantment is revealed. This is a book that has been pruned to its essentials, rather like Sally’s mother prunes her rose garden throughout the book…

Gerald Kersch Died with His Boots Unclean

One of the great chroniclers of London’s metropolitan life was the versatile Gerald Kersch (1911-1968), although he came to settle in Barbados (where his house burnt down), then Canada, and in America where he saw the last fifteen years or so of his life out (and where he had gained some success). His neteen novels – he wrote hundreds of short stories, too – are set often against a vivid, rakish and neon West End backdrop, involving spivs, streetwalkers, cut-throat razors and back-street drinking clubs. Night and the City (1938), whose anti-hero Harry Fabian wishes to become London’s leading wrestling promoter at any cost, and Fowlers End (1957, “one of the best comic novels of the century,” claimed Anthony Burgess) are impressive books; his short stories are excellent and original, and in many ways he was a latter-day English Maupassant with his nose for a popular tale and a natty idea...

One of the great chroniclers of London’s metropolitan life was the versatile Gerald Kersch (1911-1968), although he came to settle in Barbados (where his house burnt down), then Canada, and in America where he saw the last fifteen years or so of his life out (and where he had gained some success). His neteen novels – he wrote hundreds of short stories, too – are set often against a vivid, rakish and neon West End backdrop, involving spivs, streetwalkers, cut-throat razors and back-street drinking clubs. Night and the City (1938), whose anti-hero Harry Fabian wishes to become London’s leading wrestling promoter at any cost, and Fowlers End (1957, “one of the best comic novels of the century,” claimed Anthony Burgess) are impressive books; his short stories are excellent and original, and in many ways he was a latter-day English Maupassant with his nose for a popular tale and a natty idea...

Hans Fallada & Despair At Brookfield Farm

Hans Fallada was run over by a horse and cart aged 16 and then kicked in the face by the horse; he contracted typhoid a year later which led to a lifelong drug addiction, particularly morphine; troubled by public reaction to his emerging homosexuality, he botched his first suicide attempt when 18 although shot his best friend dead; he was acquitted as insane, then to spend the rest of his life in and out of asylums; also time spent in prison (never more than a three year stretch) for petty theft; relief from an unhappy marriage was sought (his attempts to murder either of his two wives failed), so he undertook a disastrous affair; his publisher fled Germany and the disapproval (even occasional imprisonment as an “undesirable writer”) from the Nazi hierarchy led to nervous breakdown, alcoholism and poor book sales; mind you, his decision to stay in Germany throughout the 1930s and then during the war led to strong criticism later from the likes of pious Thomas Mann. On the bright side he lived ’til he was 53, though his manuscripts were lost posthumously…

Hans Fallada was run over by a horse and cart aged 16 and then kicked in the face by the horse; he contracted typhoid a year later which led to a lifelong drug addiction, particularly morphine; troubled by public reaction to his emerging homosexuality, he botched his first suicide attempt when 18 although shot his best friend dead; he was acquitted as insane, then to spend the rest of his life in and out of asylums; also time spent in prison (never more than a three year stretch) for petty theft; relief from an unhappy marriage was sought (his attempts to murder either of his two wives failed), so he undertook a disastrous affair; his publisher fled Germany and the disapproval (even occasional imprisonment as an “undesirable writer”) from the Nazi hierarchy led to nervous breakdown, alcoholism and poor book sales; mind you, his decision to stay in Germany throughout the 1930s and then during the war led to strong criticism later from the likes of pious Thomas Mann. On the bright side he lived ’til he was 53, though his manuscripts were lost posthumously…

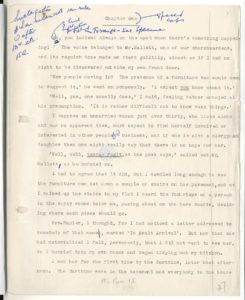

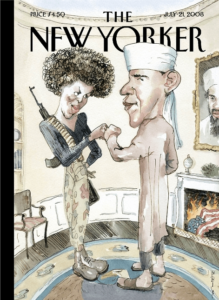

The New Yorker

The creation of The New Yorker is a true case of necessity being the mother of invention. In the early 1920s, a New York couple – Harold Ross and Jane Grant – were frustrated with the lack of sophistication in the leading magazines like Life or Judge (where Ross worked) and wanted to create their own title to fill this gap. With Raoul Fleischmann as business partner, they established in February 1925 the F-R publishing company: The New Yorker was born. Ross was famously known to have said about his magazine that it “is not edited for the old lady in Dubuque,” a sentiment reflected by E. B. White, a contributing editor to The New Yorker who, when asked what kind of submissions were wanted, is said to have replied, “I myself have only the vaguest idea what sort of manuscripts The New Yorker wants. I do have, however, a pretty clear idea of what it doesn’t want.”…

The creation of The New Yorker is a true case of necessity being the mother of invention. In the early 1920s, a New York couple – Harold Ross and Jane Grant – were frustrated with the lack of sophistication in the leading magazines like Life or Judge (where Ross worked) and wanted to create their own title to fill this gap. With Raoul Fleischmann as business partner, they established in February 1925 the F-R publishing company: The New Yorker was born. Ross was famously known to have said about his magazine that it “is not edited for the old lady in Dubuque,” a sentiment reflected by E. B. White, a contributing editor to The New Yorker who, when asked what kind of submissions were wanted, is said to have replied, “I myself have only the vaguest idea what sort of manuscripts The New Yorker wants. I do have, however, a pretty clear idea of what it doesn’t want.”…