From suburbia and skyscraper scrawl to the open prairies and 'local color', slum life to rural idyll: reprinting American and British literary classics.

Sally Bayley: Girl With Dove

“Outside of books, nothing much happens. Most of life is boring,

which is why you have to make some of it up.”

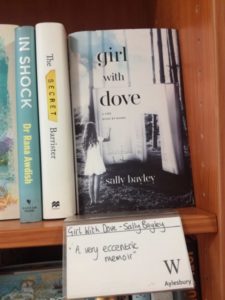

I have read recently Girl With Dove: A Life Built By Books by Sally Bayley, a childhood autobiography. Waterstone’s marketing tag for the book is that it is a “very eccentric memoir.” It might be eccentric in that it touches the eccentricities of childhood, but more likely it is very playful, certainly very different. Playful because it has been written with a sense of danger and very much composed on the hoof; there can be no blueprint for a book like this, for it has followed instinct rather than form or structure. And it is different to other memoir because its obfusc and scant narrative hovers in our sight, and as readers we can try to steady ourselves with it along the way; yet beneath a palimpsest of childhood enchantment is revealed. This is a book that has been pruned to its essentials, rather like Sally’s mother prunes her rose garden throughout the book. The storyline that is left is almost as simple and straightforward as a children’s picture book, but this only to enable us to view the world as interpreted by a child. It is quite a remarkable achievement and I urge you to go out, buy a copy and read it.

I have read recently Girl With Dove: A Life Built By Books by Sally Bayley, a childhood autobiography. Waterstone’s marketing tag for the book is that it is a “very eccentric memoir.” It might be eccentric in that it touches the eccentricities of childhood, but more likely it is very playful, certainly very different. Playful because it has been written with a sense of danger and very much composed on the hoof; there can be no blueprint for a book like this, for it has followed instinct rather than form or structure. And it is different to other memoir because its obfusc and scant narrative hovers in our sight, and as readers we can try to steady ourselves with it along the way; yet beneath a palimpsest of childhood enchantment is revealed. This is a book that has been pruned to its essentials, rather like Sally’s mother prunes her rose garden throughout the book. The storyline that is left is almost as simple and straightforward as a children’s picture book, but this only to enable us to view the world as interpreted by a child. It is quite a remarkable achievement and I urge you to go out, buy a copy and read it.

Its two main themes are childhood and the reading of books (perhaps how the two meet each other). The first has been written of endlessly since Nick Hornby and Blake Morrison; the second is now a subject of emotional, ritualised nostalgia in an otherwise forbidding digital age. Also the book melds fact and fiction, a current fad as old as the wheel. In fact this book might be accused of teetering, if only accidentally, on the edge of an intersectional commercial world. But it is unlike any other book I have ever read and is so palpably authentic as to be oblivious to any assault from fashionista. Its prose is beautiful and flowing, but even this is deceptive. It may read as an eel tricking away from its pit and before you can lunge at its tail to trace its detail, it has swum the river’s length; the reader is left spellbound and carried along in its wake. The book’s effect is cumulative therefore, the length of the river (in this case a quick read of 270 pages, hip flask size with generous margin and large font, in fact an editing marvel for Collins, who so often wear underpants outside their trousers). But beware of the book’s eddies and deviations; its fragmented momentum will leave you bewildered, gently concussed as though smitten about the head with a feather boa. Its childish hue and runic repetitions may appear simple but they are as the stretto voices in a fugue. If these voices can ever be resolved it will only be through the use of a dovetailed imagination – Sally’s in the writing, ours in the reading. Before all else this book is a heartfelt paean to the imagination.

I might read Girl With Dove as a mystery story, one that Miss Marple might have fashioned to make sense. Miss Marple is eight-year-old Sally’s heroine and a character in the book. The clues of this mystery are inherent in its beginning, described as the ‘reader’s backstory’ but told as a fairy tale in the book’s Preface, with Sally, her mother, the Lady Upstairs, the Nappy Witch and David. David is Sally’s young brother who one day, when Sally is four years old, vanishes. It is some while before we learn with certainty that David has died, although we suspect it straightaway such is the foreboding that accompanies this fairy tale.

Hereafter Sally “spills the beans” on her unusual and claustrophobic childhood: its confusion and chaos, its diet of cheese on toast, the closet characters who step out from the books she reads, the china cherubs and chandelier that erratically hide domestic squalor, and of congestion. There are eventually eleven other familial children in the house, all birthed by midwives in, we might assume, an annunciated state: this is “a family without men,” says Aunt Di defiantly to a social worker, “We’ve decided we don’t need them.” If men ever appear it is offstage and with no script (although Bill has a Toblerone). The most useful man in the book is Awful Fred and we don’t even meet him. (Actually he is dead, but his inheritance pays for the chandelier.) Also in the house are three matrifocal women. A grandmother, Maze, is in place already; after David dies “Mummy,” says Sally, “went to bed for a very long time,” collapsed in depression, and Aunt Di moves in to help. Aunt Di is the centrifugal force in the story and queen bee of the house; if she doesn’t dominate the actual text then her shadow is cast over it at all times. She is the veiled malaise that settles in amongst an already disturbed domesticity, just like the green mould that settles in the kitchen. With her arrival come net curtains, yellow clouds of smoke and black rocks spoken from the sky; also the sequence of men that Sally and her brother find draped occasionally on the living room floor like drones, presumed by the children to be dead. Aunt Di prevents Sally’s mother from marrying Laurie (Sally’s father, who appears in the book only once: to take the family to the local hotel for an evening meal of frozen grapefruit and bread and butter, described hilariously, before he is rebuffed again). She is the dark-haired lady, nexus of the Elim church that meets in the house. This cult-like gathering is never defined; clearly it made little sense to Sally’s juvenile mind, and is seen only as ring-a-ring-of-roses and Greek (speaking in tongues), but we discover that it is the dark, brooding backdrop to the disappearance of Poor Sue, a young girl with a much older husband who is part of this cult, last seen being taken away in an ambulance with her feet dangling from its back. Sue’s afterlife is a whisper of horror. She is spoken of often but nobody claims to have known her. Sue was humdrum and blurred in with everything else when alive, but she becomes a skeleton in the cupboard when dead. She pops up throughout as a jack-in-the-box: “Old stories are stubborn. You can nip and prune and cut back a bit, but you can’t easily shift their roots. The story of Sue is very stubborn.” Hers is the ultimate narrative cul-de-sac of the book.

Hereafter Sally “spills the beans” on her unusual and claustrophobic childhood: its confusion and chaos, its diet of cheese on toast, the closet characters who step out from the books she reads, the china cherubs and chandelier that erratically hide domestic squalor, and of congestion. There are eventually eleven other familial children in the house, all birthed by midwives in, we might assume, an annunciated state: this is “a family without men,” says Aunt Di defiantly to a social worker, “We’ve decided we don’t need them.” If men ever appear it is offstage and with no script (although Bill has a Toblerone). The most useful man in the book is Awful Fred and we don’t even meet him. (Actually he is dead, but his inheritance pays for the chandelier.) Also in the house are three matrifocal women. A grandmother, Maze, is in place already; after David dies “Mummy,” says Sally, “went to bed for a very long time,” collapsed in depression, and Aunt Di moves in to help. Aunt Di is the centrifugal force in the story and queen bee of the house; if she doesn’t dominate the actual text then her shadow is cast over it at all times. She is the veiled malaise that settles in amongst an already disturbed domesticity, just like the green mould that settles in the kitchen. With her arrival come net curtains, yellow clouds of smoke and black rocks spoken from the sky; also the sequence of men that Sally and her brother find draped occasionally on the living room floor like drones, presumed by the children to be dead. Aunt Di prevents Sally’s mother from marrying Laurie (Sally’s father, who appears in the book only once: to take the family to the local hotel for an evening meal of frozen grapefruit and bread and butter, described hilariously, before he is rebuffed again). She is the dark-haired lady, nexus of the Elim church that meets in the house. This cult-like gathering is never defined; clearly it made little sense to Sally’s juvenile mind, and is seen only as ring-a-ring-of-roses and Greek (speaking in tongues), but we discover that it is the dark, brooding backdrop to the disappearance of Poor Sue, a young girl with a much older husband who is part of this cult, last seen being taken away in an ambulance with her feet dangling from its back. Sue’s afterlife is a whisper of horror. She is spoken of often but nobody claims to have known her. Sue was humdrum and blurred in with everything else when alive, but she becomes a skeleton in the cupboard when dead. She pops up throughout as a jack-in-the-box: “Old stories are stubborn. You can nip and prune and cut back a bit, but you can’t easily shift their roots. The story of Sue is very stubborn.” Hers is the ultimate narrative cul-de-sac of the book.

Indeed: cul-de-sac galore. If you are looking for an authorised account of a childhood then this book fails. “Facts,” says Sally’s Mum, “are usually a bit thin on the ground,” and to be caught up in the autobiographical facts of Sally’s life is of no vital importance here. Her childhood timeline as presented is casual, interrupted and overlapped often, arranged as a series of narrative dots to be joined together by conjecture or even guesswork. The failure to resolve any of its detail is the nub of the book (for us as well as Sally) and is its great literary deceit. Throwaway serendipity – like the bulldozing of her Mother’s roses by the council (much earlier in the book we are told she had planted them on council turf, which we might have forgotten) – confirms that narrative is neither a prerequisite for this autobiography nor indeed its point. We are as confused as much by what Sally doesn’t tell us as by what she does. Mystery and, as we mature, its conquest, are tools that allow us to filter fear from the unknown. We discover in this book that the unknown is never conquered, and it makes this book a thrilling, white-knuckle read. This would be all too much even for Miss Marple.

Indeed: cul-de-sac galore. If you are looking for an authorised account of a childhood then this book fails. “Facts,” says Sally’s Mum, “are usually a bit thin on the ground,” and to be caught up in the autobiographical facts of Sally’s life is of no vital importance here. Her childhood timeline as presented is casual, interrupted and overlapped often, arranged as a series of narrative dots to be joined together by conjecture or even guesswork. The failure to resolve any of its detail is the nub of the book (for us as well as Sally) and is its great literary deceit. Throwaway serendipity – like the bulldozing of her Mother’s roses by the council (much earlier in the book we are told she had planted them on council turf, which we might have forgotten) – confirms that narrative is neither a prerequisite for this autobiography nor indeed its point. We are as confused as much by what Sally doesn’t tell us as by what she does. Mystery and, as we mature, its conquest, are tools that allow us to filter fear from the unknown. We discover in this book that the unknown is never conquered, and it makes this book a thrilling, white-knuckle read. This would be all too much even for Miss Marple.

Facts are not hidden from this book as a figment of repression or to preserve the psychosomatic comfort of the storyteller (though some may be hidden to be mindful of those involved still alive). Well there are a few facts: Charles I is the king who “had his head chopped off,” Grasmere is where Wordsworth wrote ‘Daffodils’ (“Mum’s favourite poem”), Sompting “is a place in Sussex next to Lancing” – these are recited as the discovered patois of the child, debris accumulated in Sally’s mind to help make sense of her world, to make it appear real and tactile. Crucially the absence of much hard fact allows us to see through the eyes of the child and not through the memories of childhood. This is the voice of child we are reading. Only in the final section when – as Sally says, “I am starting to sound like an adult” – is the flow interrupted by overt retrospection or is the book’s meagre storyboard amplified with knowledge acquired by Sally the elder.

Childish tics are the carefree splurge of primary colour throughout the book’s canvass. The descriptive language is distilled to similes of Sally’s limited experience (Audrey, for instance, who is the social worker described as a medieval saint, is likened to “a piece of toffee that someone had chewed on for a while”); knowledge is expressed often through the English mannerisms assumed from her mother (as an aside, I warmed to its expressions: kings and queens of England learnt by rote, Queen Victoria and later abdication, the anarchy of Scargill’s tatty anorak set against Margaret Thatcher’s authoritative deliberation and string of pearls, patterns on tea cups, rose gardens, vicars, the seaside and its mythology, Agincourt mapped out in iambic pentameter underneath the chandelier by Colonel Stapley who is the home Shakespearean tutor, and, of course, all that is English in Agatha Christie’s village landscape, “days that never were”). Throughout we are voyeurs to Sally’s maturing and real time sensations; we watch them by ourselves with no annotation from an adult narrator. When we read that Sally daren’t call Sue small and plain (“but someone else might,” she says), we read how really she is not yet brave enough to test this social boundary (or perhaps she has learnt not to be too cruel); we sense Sally’s disorientation as figures of authority – librarians or the doctor’s receptionist – admonish her; and we witness Sally display flashes of dissent, when, for instance, she refuses to salute Colonel Stapley. Visual concerns are those of the child’s tabletop eye-level (handbags, of course, biscuits dunked, the game the children play as they shimmy atop the furniture and window ledges to keep themselves from the floor), or are centred upon objects of fear and the unknown (curtains, from behind which not only diabolical aunts appear but also spiders and witches, or the white door at the top of the stairs). Also there are the immense stretches of childish logic that fire as a blunderbuss, are runaway and conclusive (Mr Robinson in the top floor flat is a “big, fat liar,” he murdered his wife, for sure). All of these are trolls to draw us into the mind of Sally the child.

The restricted, fixated vocabulary used in the book is, of course, the repetition of childish observation and obsession; there are many leitmotif objects and themes that pepper each page of the book, these weaved into a literary threnody of innocence and choked wonderment. A fairy pinches a small rosebud mouth to stop it from crying out loud; very soon Sally’s grandmother is pinching peas. So many coincidences, so many Marys (Sally’s middle name, she tells us proudly several times), each mantric in design. And when this iteration stops – it certainly has by the time we negotiate the book’s final section, where Sally puts to use her innate rebelliousness by finding her own way top the doctor in Maltravers Drive and ultimately away from the family coven – we miss it. The writing hitherto has wrapped itself around us as beautiful and repetitive swaddling prose.

Likewise colours thread through the text as recitative. There is colour enough to make a painter’s palette seem sub fusc. White is the book’s whirligig, splashed like confetti upon its pages: white muslin veils, white mantilla veils, white crochet cardigan, whites of eyes, a white dove, white as the milk in a cup of tea, white linen, a fat white bloke, all sorts of white, and, of course, the white cotton nappies which the very young Sally, standing on a stool in the kitchen, would stir often with a wooden spoon in a saucepan full of scalding hot water, described at the very beginning in the reader’s backstory. There is an abundance of pink: the roses and rosebuds  in the Edenesque garden of Sally’s mother, the chaise-lounge, the hat that Sally’s mother exhorts her to wear (pictured in pink on Sally upon the book’s cover). Plenty of brown too, the colour of the lacklustre and the unadorned; Poor Sue is seen as brown. Black is for Aunt Di and the infernal. In the third, last section of the book when the colour red is introduced overwhelmingly, the writing and its tempo change. Red is the colour of the room that Jane Eyre is sent to as punishment, when she has been exposed as evil by her Aunt, to be dispatched to Lowood School. Now Sally is a young teenager, soon to be exiled to Colwood, a children’s home where she is torn asunder from both family and books. She has been “telling tales” says Aunt Di, and is expelled from the family; “sent to Coventry,” says Sally, and in an oblique childish association she remembers it to be a “nasty town:” her Mum had told her it was made of “grey concrete.” Grey is the colour of the ruined nappies before they are returned to white. Sally is ruined.

in the Edenesque garden of Sally’s mother, the chaise-lounge, the hat that Sally’s mother exhorts her to wear (pictured in pink on Sally upon the book’s cover). Plenty of brown too, the colour of the lacklustre and the unadorned; Poor Sue is seen as brown. Black is for Aunt Di and the infernal. In the third, last section of the book when the colour red is introduced overwhelmingly, the writing and its tempo change. Red is the colour of the room that Jane Eyre is sent to as punishment, when she has been exposed as evil by her Aunt, to be dispatched to Lowood School. Now Sally is a young teenager, soon to be exiled to Colwood, a children’s home where she is torn asunder from both family and books. She has been “telling tales” says Aunt Di, and is expelled from the family; “sent to Coventry,” says Sally, and in an oblique childish association she remembers it to be a “nasty town:” her Mum had told her it was made of “grey concrete.” Grey is the colour of the ruined nappies before they are returned to white. Sally is ruined.

Stitched into the text is Sal’s addiction to reading: books represent her truancy from the real world. Their characters are invited to share centre stage with her family members (not so many, Aunt Jayne visits occasionally). These bookish, surreal characters shoehorn themselves at every opportunity into her early timeline. Verity Hunt and Miss Temple step from the pages of Agatha Christie’s Nemesis to be neighbours, and both Sally’s Mum and Clotilde, Miss Marple’s would-be fictitious murderer, talk of garden flowers. The book at times appears confusingly to be set in Miss Marple’s St Mary Mead rather than in Sally’s real life English coastal village. This because reading is her escape from the drab, consumptive landscape of home with its filthy carpets and flapping back door; she welcomes these persona as they invade her life from the books she is reading voraciously. Sally is to be found in the surrounding woodlands and fields or on the floor of the public library reading. Reading alongside Jane Eyre, who is Sally’s closest, most sympathetic and most real friend, her escapologist example. Or Sally is reading alongside Helen, Jane’s clever friend. Very quickly we have accepted this shapeshifting world, and when Helen, in conversation with Sally, refers to Miss Temple, we have become so mesmerised by fable that we do not assume it is Jane Eyre’s school superintendent any more than Agatha Christie’s retired headmistress. There are many such schizophrenic moments latticed within the text. Unaffectedly these literary manikins inhabit the same narrative as Sally, an artifice I can’t recall to have been undertaken elsewhere with such brilliance. Its effect is to open our eyes to the antidotal imagination which Sally uses to breathe colour into her real world. “Imagination can turn your grey house into a bower of flowers,” notes Sally.

For all the book’s bleak aspect and its submerged misery and morbid distractions, it is replete with joy: “Speak for yourself,” says Sally, “but I’m a laughing sort of person,” and its denouement is testimony to this. Rarely before have I felt such excitement as a book closes. As it unwinds, the book displays an unnerving habit to somehow let you know that all is to be released in a final burst of order, this to be transmitted as jaw-dropping, spine tingles of affirmation. With a holla of joy I read its last pages, as I realised that I had been embraced by Sally Bayley’s imaginative span.

For all the book’s bleak aspect and its submerged misery and morbid distractions, it is replete with joy: “Speak for yourself,” says Sally, “but I’m a laughing sort of person,” and its denouement is testimony to this. Rarely before have I felt such excitement as a book closes. As it unwinds, the book displays an unnerving habit to somehow let you know that all is to be released in a final burst of order, this to be transmitted as jaw-dropping, spine tingles of affirmation. With a holla of joy I read its last pages, as I realised that I had been embraced by Sally Bayley’s imaginative span.

“…imagination radically alters things. It changes outlooks and aspects, of people and places, moods and feelings, even the very end of things, who marries who. Imagination can turn your grey house into a bower of flowers. But once you let it in, it is bound to turn you out of doors. Imagination will soon send you packing into the wide green world.”

Earlier in the book Sally remembers a photograph of Maze on the beach wearing white gloves; as she gazes at it, she wishes to take the gloves off and feel the wet soft soap bubbles on Maze’s fingers. She then recites from David Copperfield, where David remembers “an impression on my mind which I cannot distinguish from actual remembrance,” to touch Peggotty’s forefinger, roughened “like a pocket nutmeg-grater.” Sally’s lesson is that to touch the real, to peel the impression from a remembrance, we need the artifice of imagination. If photographs portray the real, then they are but chimera. Mirrors likewise mislead for, says Maze, they “never tell the truth.” The portrayal of the real world, the accumulation of fact, the facts themselves, can teach us very little. It is always the imagination that transports us and sets us free:

“When you read a book like Jane Eyre, you start to see things, small fragments of this and that that shoot across your eyes like stars. Tiny pictures appear in between the pages as you turn them. You begin to see and hear things: a woman’s smile, a woman’s laugh, a woman with her hands held high, a woman speaking gobbledygook. And then suddenly, without warning, you are in Lancing on Sea a long time ago and you don’t know how you got there. Some strange spirit has carried you away.”

The expression of our past is so often philopatric or chronological, snatched moments of place or time. Yet it is the imagination that makes it breathe. The attempt to show us this must have been for Sally the writer a dangerous and bumpy literary toboggan ride down a steep face of the Eiger. If her dangerous ride fails to maintain its momentum at every twist, or if we find ever our concentration wavering (I found the Shakespearean drama scene set in the children’s home lacklustre), it is just part and parcel of a book like this. What matters most is the arc of its journey: the intent of this book is almost all that matters.

Girl With Dove is a courageous example of form in free fall: just as you get comfortable with it, as soon as it begins to make sense, there is a nosedive from the unexpected and it bellyflops like an elephant in shallow water. With this book we come to understand what it is we are in danger of losing if we are not careful, as we progress from childhood into adulthood. As we replace hair slides (in Sally’s case) with visits to the hairdresser (still not so, in Sally’s case), or short trousers and romance with long trousers and experience, as we traffic the raw and the immediate for caution and the considered, as we realise that imagination can always triumph. The specific of Sally’s experience was the reading of books, and these books saved her. Within them she found missing people even: “Jane Eyre, who reads a lot of books,” marvels Sally, “calls these natural sympathies.” If we are lucky this may have been part of our own rich life experience. But this book shares with us much more than this. Girl With Dove is a bold attempt to highlight the lack of boundaries within the childish mind, that desire to dig behind reality and to find the imaginative that can protect us from the real. In Sally’s case its result is her burst of freedom: she escapes to Maltravers Drive with its big houses, gravel driveways, and its doctor’s surgery.

I allowed my first read of this book to comprise two sittings, annoyingly with a week’s interlude; I wish now that I had read it at one gallup so that its pulse could carry me alongside. So much contained in its beginning proves to be a vital clue for its later reading. Throwaway text is passed on as a relay baton throughout the book, and for this reason it pleads to be read again so that you can pick up the clues that fell to the floor on a first reading.

Girl With Dove is a wonderful book. It turns the grey into a riot of colour.

‘BEST OF’ MOMENTS:

“Letters are hidden hurricanes sealed away in small white parcels.”

“Women waft about in nighties when things are going wrong.”

“If you want to be a poet you have to know how to pray.”

“Nobody says drapery when they mean curtains.”

“History is remembered by a series of smiles.”

“History is full of hand-me-down projects.”

Sally Bayley’s previous book was The Private Life of the Dairy [Unbound Books, 2016]. In it we learn that pea and cereal cow feed makes high quality, high yield silage (so much better than maize): farmers need to be told. Not really. It’s actually a coming of age story through diary writing, and mixes memoir with commentary on the famous diarists.

Sally Bayley’s previous book was The Private Life of the Dairy [Unbound Books, 2016]. In it we learn that pea and cereal cow feed makes high quality, high yield silage (so much better than maize): farmers need to be told. Not really. It’s actually a coming of age story through diary writing, and mixes memoir with commentary on the famous diarists.