From suburbia and skyscraper scrawl to the open prairies and 'local color', slum life to rural idyll: reprinting American and British literary classics.

Gerald Kersch Died With His Boots Unclean

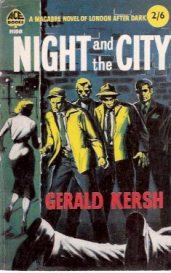

One of the great chroniclers of London’s metropolitan life was the versatile GERALD KERSH (1911-1968), although he came to settle in Barbados (where his house burnt down), then Canada, and in America where he saw the last fifteen years or so of his life out (and where he had gained some success). His neteen novels – he wrote hundreds of short stories, too – are set often against a vivid, rakish and neon West End backdrop, involving spivs, streetwalkers, cut-throat razors and back-street drinking clubs. Night and the City (1938), whose anti-hero Harry Fabian wishes to become London’s leading wrestling promoter at any cost, and Fowlers End (1957, “one of the best comic novels of the century,” claimed Anthony Burgess) are impressive books; his short stories are excellent and original, and in many ways he was a latter-day English Maupassant with his nose for a popular tale and a natty idea. Some of these ideas moved into popular mythology – his story about the Mona Lisa’s poor teeth, for instance, hence her lack of a smile. After his death Kersh’s literary star fell from grace; but the revival of interest in British gangsters, particularly as popular film fodder (Bob Hoskins’ trademark, even Robert de Niro got to star in a boxing remake of Night & the City in 1992), has allowed Kersh minor cult status. Many of his books have been reprinted recently.

The books smack of autobiography; they contained, he wrote, “an irreducible minimum of made-up-stuff.” Kersh was a bit of a bruiser and he sported the usual telltale signs of the bar pugilist: a tooth mark patina on his right knuckles caused by a fist fight, a knife slash on his left wrist, so on, and he suffered a lifelong concussion, the result of a fight involving a marbletop table and a sixpenny hatchet (not quite the props of Cluedo); sometimes he slept rough. Kersh was dedicated to writing however, a career he determined from a tender age. As a child he offered critical advice to Edgar Wallace, suggesting that he wrote better than Wallace yet simultaneously asking for his advice. Wallace’s reply was peremptory.

The books smack of autobiography; they contained, he wrote, “an irreducible minimum of made-up-stuff.” Kersh was a bit of a bruiser and he sported the usual telltale signs of the bar pugilist: a tooth mark patina on his right knuckles caused by a fist fight, a knife slash on his left wrist, so on, and he suffered a lifelong concussion, the result of a fight involving a marbletop table and a sixpenny hatchet (not quite the props of Cluedo); sometimes he slept rough. Kersh was dedicated to writing however, a career he determined from a tender age. As a child he offered critical advice to Edgar Wallace, suggesting that he wrote better than Wallace yet simultaneously asking for his advice. Wallace’s reply was peremptory.

To support his early writing career he was at times a bodyguard, debt collector, an all-in wrestler, a cinema manager, a travelling salesman (selling “anything from sausages to electric lights”), a cook in a fish and chip shop. Kersch could hold his own in any situation. His first novel was published in 1934. Jews Without Jehovah, the tale of a Jewish family that was so autobiographical that three uncles and a cousin filed a libel suit: although the book had received good pre-publication notices, it was withdrawn from sale within its first day. Family gatherings thereafter, even when other cheeks had been turned, remained tense! He was  a prolific and promiscuous writer. He wrote scripts for the Army Film Unit; he wrote as Piers England during the Second World War for The People, a series called The Private Life of A Private for the Daily Herald, wartime propaganda par excellence, much else under other untraceable pseudonyms. They Died With Their Boots Clean (1941) was a novel that emerged from a pamphlet he was writing on military training, commissioned by the Home Office. He wrote comedy scripts for the B.B.C. also. In the meantime Night and the City was sold for £40,000 film rights (the scripts he perused were so distant from the book that he boasted that he had been paid £10,000 per word, or rather £10,000 for each word of the title – the only part of the book that remained intact); the book was filmed first in 1952 starring Richard Widmark and Gene Tierney.

a prolific and promiscuous writer. He wrote scripts for the Army Film Unit; he wrote as Piers England during the Second World War for The People, a series called The Private Life of A Private for the Daily Herald, wartime propaganda par excellence, much else under other untraceable pseudonyms. They Died With Their Boots Clean (1941) was a novel that emerged from a pamphlet he was writing on military training, commissioned by the Home Office. He wrote comedy scripts for the B.B.C. also. In the meantime Night and the City was sold for £40,000 film rights (the scripts he perused were so distant from the book that he boasted that he had been paid £10,000 per word, or rather £10,000 for each word of the title – the only part of the book that remained intact); the book was filmed first in 1952 starring Richard Widmark and Gene Tierney.

His writing is fittingly fruity (Zoe, the prostitute in Night and the City, had breasts that rapidly swelled to a “flaccid over-ripeness in a humid atmosphere of eroticism, like tomatoes in a hothouse”), and it rejoices in cartoon violence (“the machine-gun in Fabian’s imagination gave a last, vicious stutter”). A reader can register moral disapproval very easily which makes the books engaging. But it is Kersh’s poor aesthetic taste that wins the day, and this at times is endearing. Later in his life, always the recusant and several steps from virtue, his income tax returns were filed late and with scant regard for accuracy, more fictitious in fact than his fiction. Gerald Kersh’s tax returns offer proof that there is a novelist in all of us.