From suburbia and skyscraper scrawl to the open prairies and 'local color', slum life to rural idyll: reprinting American and British literary classics.

Barbara Pym

It’s The Church Pew That Moves, Not The Earth

You have to be bonkers not to love Barbara Pym’s novels. Her acme was a 1950s suburban or neo-rural setting where The Archers doesn’t quite meet James Bond, because you don’t get the offstage milking of cows, and if the tea is stirred, well, it’s never shaken… Her plots thrive off crinoline and a matching cruet set, cups of tea always, gallons of the stuff, but also sheer delight. They offer welcome shelter from today’s boorish age: the best bookshops lay out her books as though pots of jam on display at the local church fete.

You have to be bonkers not to love Barbara Pym’s novels. Her acme was a 1950s suburban or neo-rural setting where The Archers doesn’t quite meet James Bond, because you don’t get the offstage milking of cows, and if the tea is stirred, well, it’s never shaken… Her plots thrive off crinoline and a matching cruet set, cups of tea always, gallons of the stuff, but also sheer delight. They offer welcome shelter from today’s boorish age: the best bookshops lay out her books as though pots of jam on display at the local church fete.

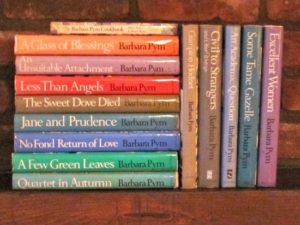

The whole thing about Barbara Pym is that it’s a sort of aesthetic experience as well as a literary one; she is best read whilst tea is brewing in a teapot and a scone is fresh out of the oven. She is a retro-themed lifestyle statement, and over the years – even when she was neglected and largely unread (publisher Jonathan Cape turned their back on her), before Philip Larkin re-invented her and she was able to have a late-life stab at the Booker Prize – publishers suitably doffed their (not so starchy) table doily design caps her way. Some of her books’ dust covers are wonderful, delightful and suburban. Because it just felt right – Dutton published her in America, covers designed by Jacqueline Schuman that were ‘wallpaper’ themed, so apt – but because there’s always more to Barbara Pym than the written words.

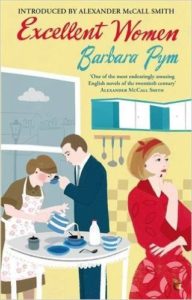

So a for instance. Excellent Women was the second of Barbara Pym’s novels to be published (in 1952), cited often as the wittiest. It is an Anglicanized and a more gentle, parochial version of the Keystone Cops: no truncheon or police car siren of course, but a true comedy of manners that revolves around mistake, mishap and flaw. Its title derives from a condescending reference to the neo-deferential class of women do-gooders of post-war middle class Britain. This neo-deferential lot are bog-standard Pym characters. An equivalent would be walk-on character parts in Mrs Dale’s Diary – the afternoon Light Service (now Radio 2, spit) soap opera which ran for 21 years from 1948, for which my Aunty Joan would down all her whipping cream utensils and dusters to listen to. Mrs Dale’s Diary had Metroland doctors’ waiting rooms and middle class medicine as banter rather than Pym’s gossip of jumble sales, local church politics, sewing hems on skirts, single ladies being ‘on the shelf’ at 29, tea and scones. (Incidentally both this early radio soap opera and Barbara Pym – A Glass of Blessings – were forerunners in acknowledging gay sensibilities at more or less the same time.) As is always the case with Pym, the plot is only the skeleton upon which hangs the torso of a latter-day Jane Austen: superficial social natter and clatter, but really a palimpsest of social irony, social tragedy, desire, so often unrequited and unspoken, all that sort of stuff, the stuff that makes us frail and embarrassed to be human, indeed the whole social condition, and with Pym it’s written about with sonority and percipience. The honesty is nowhere near naff, for Pym is so true that her books are like arrows to our secret heart.

Her great literary rival in retrospect is Angela Thirkell. (Her books were set in Trollope’s Barsetshire. I’ve known loads of churchwardens’ wives who’ve collected her books over the years as though hymn books. They were so easy to sell second-hand at silly prices, so long as they had a dust cover and so long as you priced them just under the value of the church collection the previous week.) Thirkell’s writing got more engaging after slightly disastrous early attempts (my schoolmaster’s report – could’ve done better), but it never came close to Pym for subtlety. Earlier variants like E. F. Benson disappoint in comparison (can only read one at a time, gotta slip in something racier in-between) and later exponents of a sort of Pym derivation – the pastel shaded covers of 1990s, observant women’s fiction – tripped over the bar that Pym set too high: Mary Wesley and her acolytes were so hollow in comparison (it’d be like comparing Robert Ludlum to Robert Louis Stevenson, just can’t do it, a man with one wooden leg always wins). In short, Pym’s writing is so well crafted that it is impossible to see its glue, and her depiction of life and character sizzles with delight.

And there you are, your own social stumbling and naivety perfectly described in her books – perhaps with hair bun or hairnet washing up after the Church Christmas bazaar, or visiting a quarrelsome parishioner dressed as a country vicar with a letter of introduction from the bishop. And if you don’t get to like Pyms’ writing once you’ve started reading it, well you’re just nuts, and it’s probable that Barbara Pym’s doily napkins that flutter in the kitchen pantry at night – they must exist, they’re probably for sale next to the pudding basins in any good department store – will put a dead fly in the jam you spread on to your scone. Or I will…

![]()

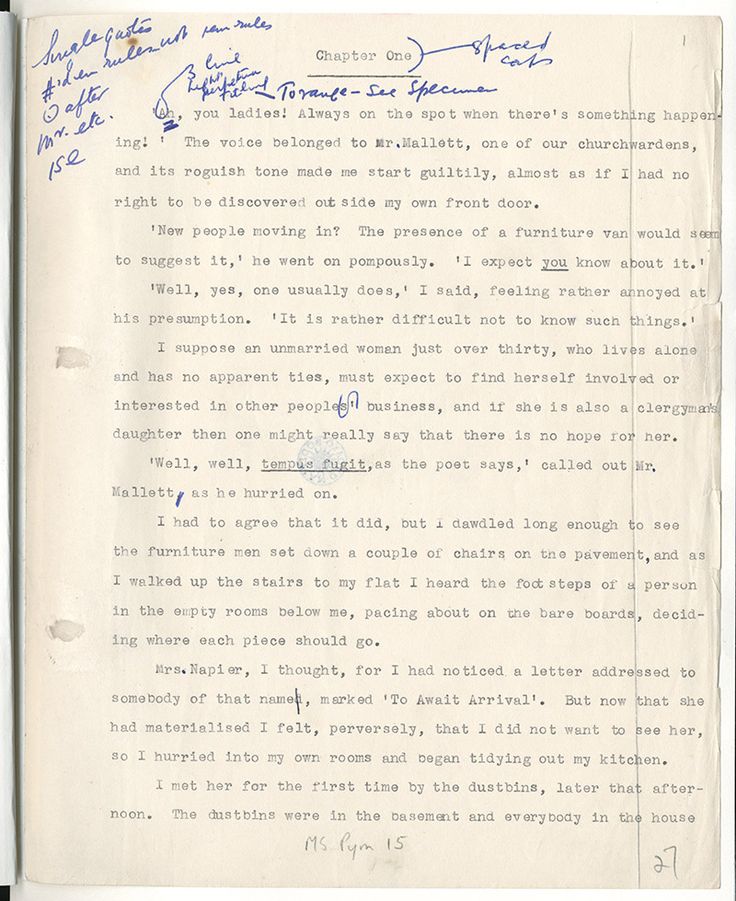

So in this naff video I get to identify as a spinster, a bit starchy coz am a clergyman’s daughter, rather prone to fantastical romance, though I sort of get my end away with an anthropologist before the book closes (though it’s the church pew that moves, course, not the earth): a reading from the opening page of Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women, narrated by its heroine, Mildred Lathbury. (The text is below.) I don’t identify that well, have to say, hence the tea spilt in the saucer (note that the cup and saucer don’t match, the real Mildred would never have allowed that, not for guests anyway), my cacophonous spoon tapping, the pub patois at the end, the hairy, unkempt fingers, the size 12 denture mark on the lemon drizzle cake, though I did shave this morning coz probably Marlon Brando’d have done that (it’s called method acting, though bugger the bit about tidying the kitchen).

![]()

BARBARA PYM’S BIOGRAPHY

Barbara Pym was born in Oswestry, Shropshire in 1913. Her first attempt at writing was as a youthful sixteen year-old, Young Men in Fancy Dress (1929) which is held at the Pym Archives at the Bodleian Library. In 1931 she entered St. Hilda’s College, Oxford, where she obtained a second class honours degree in English. She then returned to Oswestry and completed Some Tame Gazelle in 1935, which was submitted to publishers but not accepted. This book shows her developing style – witty, elegant, humorous and sympathetic to her characters. She imagines herself and her sister as they will be in thirty years time, and weaves in her friends from Oxford.

She worked for the Censorship office in Bristol during World War, followed by a spell in the WRNS, mostly in Naples. During this time she recorded all that passed in her notebooks in preparation for her novels. One of the naval officers she knew was used as a basis for Rocky Napier in Excellent Women. She recorded post-World War II upper middle class life, with both elegance and satire, and with great insight into her characters. Her first published novel, Some Tame Gazelle (published in 1950), was followed by five more books.

In 1963 her publisher rejected An Unsuitable Attachment, as it was felt that they could not sell enough even to cover costs. Her early success did not continue as she failed to find a publisher for her new novels. Despite the resulting gloom, she carried on writing and produced The Sweet Dove Died, in which the heroine attempts to gather a younger man into her life – presumably based on her own relationship at forty-nine with a thirty-two year-old man: it too was refused. A turnabout occurred when in 1977 Lord David Cecil and Philip Larkin both nominated her as the most underrated writer of the century. Immediately Quartet In Autumn was nominated for the Booker Prize, and The Sweet Dove Died (published finally in 1968) was critically acclaimed, although previously unaccepted by any publisher. She retired from the African Institute in London in 1974, having worked there editing its journal Africa since 1946. She never married, and moved in with her sister when she retired and until her death from breast cancer in 1980.

Her writing was of the ordinary person leading an ordinary life, drawn from a lifetime of observation. She paid more attention to style and characterisation then to story line, and she focused on social manners – particularly concerning the church community in either village or suburban life. And if her novels were written in a completely different era and were to become unfashionable to publishers, her novels stand the test of time, for human nature – and she portrays it so succinctly – never changes (well if you’re Anglican it doesn’t).

![]()

And what a wonderful glimpse into Mildred’s persona in this passage: “I must have dropped off to sleep at this point, for the next thing I knew was that I had been woken up by the sound of the front door banging. I switched on the light and saw that it was ten minutes to one. I hoped the Napiers were not going to keep late hours and have noisy parties. Perhaps I was getting spinsterish and ‘set’ in my ways, but I was irritated at being woken. I stretched out my hand towards the little bookshelf where I kept cookery and devotional books, the most comforting bedside reading. My hand might have chosen Religio Medici, but I was rather glad that it had picked out Chinese Cookery and I was soon soothed into drowsiness.” – from Excellent Women

![]()