Biography

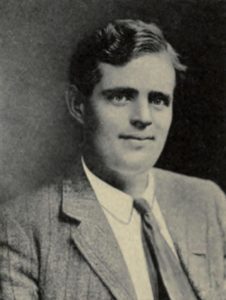

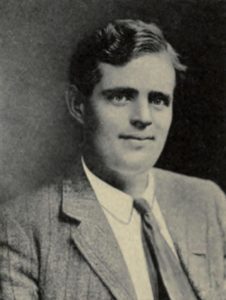

Jack London in 1909

JACK LONDON (1876 – 1916) was an American novelist, short story writer, journalist and social activist. He came from a poor background, and as a writer he was mostly self-taught. Throughout his life he advocated socialism, unionization, and workers’ rights. He was published first in 1898, and became one of the first writers to gain worldwide celebrity. It was recognised that he was the best-paid writer of his time. Jack Londonʹs most remembered books are Call of the Wild, Sea Wolf and White Fang, romantic tales of struggle and heroism. But his writing encompassed a variety of genre. The Iron Heel (1908) is one of the earliest dystopian novels, and he wrote also some of the earliest examples of science fiction. He wrote usually of his own experiences. He wrote of his time as a vagrant in the East End of London in The People of the Abyss (1903), and of his various occupations, both at sea and on land, including time spent in the Klondyke during the Gold Rush. In his later life he suffered from dysentery and alcoholism, and died in 1916 from uremia and an overdose of morphine, though speculation that he committed suicide is sentertained still by some.

London & boxing

Boxing was the up and coming sport of late nineteenth century America. The sport’s dynamic since the 1850s had shifted from England to America: both the last bare-knuckle world title fight in 1889 and the first fight under the Marques of Queensberry Rules in 1892 had taken place on American soil. As in Britain, it had become a sport to indulge all classes of society, helped by its acceptance of a rule book and a governing body. It had allied itself with the fashionable masculine personal development and good health (it was referred to often as either the noble art or the sweet science), or Teddy Roosevelt’s token vision of the “strenuous life,” the recovery of masculinity from a mechanical and toxic fume-filled urban lifestyle that had pitched the morality of the Boy Scouts or the faux, bijou wilderness of the National Parks as compensation for the closure of the frontier. The progress from bare-knuckle to Queensberry Rules made boxing consistent with the emerging sports culture of early twentieth century America; it was now a sporting spectacle as well as an opportunity to bet. This, unfortunately, was also its Achilles’ heel. After the Johnson Jeffries bout, Roosevelt withdrew his support for the sport and lambasted it as too violent and with still too large an immoral hinterland. Commercially though and rather conveniently, the sport had come to prominence when cine film and an excited cinema audience clamouring to watch it came of age. If still outlawed in many states, the sport had tried hard to refine its respectability, particularly in California where London was settled mostly.

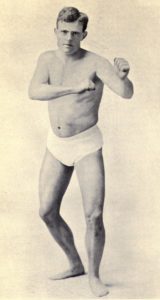

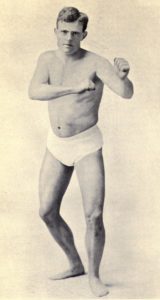

Jack London’s delinquency at school had developed into bar room brawls later in life. He was consistently pugnacious, as were many others from his background. Recreational rumpus was a method of relaxation, particularly at times of stress. When a daughter died several days after she was born in 1910, London sought refuge in a bar brawl with an Irish saloon manager; both spent the night in jail, accusing each other of assault, though neither were charged. This fracas was one night before London was to travel to Reno to cover the Johnson and Jim Jeffries fight; one local newspaper wag commented wryly that London had wanted to be Jack Johnson’s challenger “if Jeffries takes the count.” But its formal counterpoint – sparring in the gym – had started when London was twenty years old. He had learnt to box when a member of the Socialist Labor Party, in Oakland in 1896; a fellow member, Herman ‘Jim’ Whitaker, had taught him, and he frequented the gym for most of his life thereafter. He befriended boxers, the great champion Bob Fitzsimmons and Jimmy Britt in particular. Although only 5 foot 7 inches tall, he was proud of his physique when younger and expressed general interest in physical fitness; his later ill health and torpor distressed him. He equated boxing with ruddy health and fitness. When returning from Australia on his boat, recuperating from pellagra, sparring on deck was his means of “getting into condition.” He told a reported in an interview of 1911, that of “all the games, it is the only one I really like.”

Jack London’s delinquency at school had developed into bar room brawls later in life. He was consistently pugnacious, as were many others from his background. Recreational rumpus was a method of relaxation, particularly at times of stress. When a daughter died several days after she was born in 1910, London sought refuge in a bar brawl with an Irish saloon manager; both spent the night in jail, accusing each other of assault, though neither were charged. This fracas was one night before London was to travel to Reno to cover the Johnson and Jim Jeffries fight; one local newspaper wag commented wryly that London had wanted to be Jack Johnson’s challenger “if Jeffries takes the count.” But its formal counterpoint – sparring in the gym – had started when London was twenty years old. He had learnt to box when a member of the Socialist Labor Party, in Oakland in 1896; a fellow member, Herman ‘Jim’ Whitaker, had taught him, and he frequented the gym for most of his life thereafter. He befriended boxers, the great champion Bob Fitzsimmons and Jimmy Britt in particular. Although only 5 foot 7 inches tall, he was proud of his physique when younger and expressed general interest in physical fitness; his later ill health and torpor distressed him. He equated boxing with ruddy health and fitness. When returning from Australia on his boat, recuperating from pellagra, sparring on deck was his means of “getting into condition.” He told a reported in an interview of 1911, that of “all the games, it is the only one I really like.”

Journalism

Jack London himself had covered the sport as a journalist before he had written any fiction on the topic. As early as November 1901 he was covering James L. Jeffries’ world title fight against Gus Ruhlin for the San Francisco Examiner [included in this book], and his colourful reportage continued for more than the next decade and included many of the top fights of this era. His travel itinerary had in 1908 had been disturbed by illness, and he was accidentally well placed to witness Jack Johnson defeat Tommy Burns in Rushcutters Park, Sydney, suitably on Boxing Day. Ever since John L. Sullivan had declared his own “color line” in 1892 – “I will not fight a negro” – heavyweight boxing was a sport contested at the highest level by whites only, a closed shop. Johnson became the first African American to be allowed to fight for the world heavyweight crown, simply because the boxers current were lacklustre and without personality: the sport was temporarily in the doldrums. Johnson wasn’t supposed to win, of course, and it was Jack London who, in response to this affront of national white pride, called for the return of the great retired and undefeated champion James L. Jeffries, the “Great White Hope,” to defeat Johnson.

London’s reporting of Johnson’s match against Jeffries in 1910, billed as the first “Fight of the Century,” was masterful. Johnson’s win which triggered race riots in more than 25 states and 50 cities all across the United States. Circumstances had made him reluctant to go to the bout. He had lost his first child the night before he was due to travel but, after a night’s drinking and a bar brawl which saw him spend the night in jail, he set to. The fight had been stopped from taking place on his doorstop in San Francisco, but a license had been sought to hold the fight in Reno. He had arrived ten days before the fight in the pay of The New York Herald, although his coverage over ten days was syndicated to The San Francisco Call and The Australian Star. His writing for the ten days before the fight depicts a melodramatic and colourful scene, London heightening every tension with both skill and conviction. This event was a true spectacle, even Al Jolson was there as a special correspondent.

Fiction

Jack London was the first American novelist of note to write about boxing in any literary sense. He would have been very aware of boxing’s recent pedigree in fictional form. Both Bernard Shaw’s Cashel Byron’s Profession and Arthur Conan Doyle Rodney Stone had been published in 1896; the former had become a bestseller in the United States. After London’s literary attempts – two novellas and two short stories – the boxing ring and its peripheral, shadowy world was the setting for a plethora of novels.

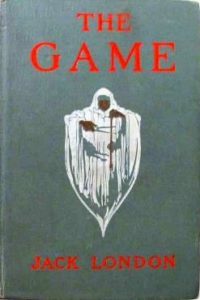

The Game, London’s first boxing novella, was written in 1905. It had started life as a short story. George P. Brett, London’s editor at Macmillan Co., enthusiastically recommended a series of such boxing tales. London preferred to develop the love story between Joe and Genevieve, and it took shape as a novella. It was published first in two issues of Metropolitan Magazine in April and May, and in four issues of The Tatler in Britain. Macmillan published in June, 1905, a revised version with additions, illustrated by Henry Hutt and T. C. Lawrence. Over 26,000 copies were registered for the first printing, and it was reprinted later that year in September. Reviews were generally favourable, although sales were not anywhere approaching those for The Call of the Wild and The Sea-Wolf from the previous two years. This book allegedly persuaded world champion Gene Tunney to retire from boxing in 1928.

The Game, London’s first boxing novella, was written in 1905. It had started life as a short story. George P. Brett, London’s editor at Macmillan Co., enthusiastically recommended a series of such boxing tales. London preferred to develop the love story between Joe and Genevieve, and it took shape as a novella. It was published first in two issues of Metropolitan Magazine in April and May, and in four issues of The Tatler in Britain. Macmillan published in June, 1905, a revised version with additions, illustrated by Henry Hutt and T. C. Lawrence. Over 26,000 copies were registered for the first printing, and it was reprinted later that year in September. Reviews were generally favourable, although sales were not anywhere approaching those for The Call of the Wild and The Sea-Wolf from the previous two years. This book allegedly persuaded world champion Gene Tunney to retire from boxing in 1928.

A Piece of Steak was written for the Saturday Evening Post in 1911, though written in 1909.

The Mexican was written during the Mexican Civil War and is as much a propagandist tract in favour of the revolution as about boxing. It was published by the Saturday Evening Post in 1911, and came out in book form two years later in a collection of Storie called The Night Born. It was filmed in 1952 as The Fighter with Richard Conte and Lee J. Cobb (and it as filmed also in the Soviet Union in 1956).

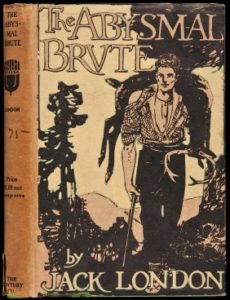

The Abysmal Brute was published first in Popular Magazine in 1911 and was written in October 1910; it was published in book form in 1913 by the Century Company. It was influenced greatly by his coverage of the Johnson-Jeffries fight that had taken place on 4th July in Reno. Pat Glendon was based on Jack Johnson: Glendon’s walk was “smooth and catlike.” And Glendon had pursued Tom Harrison to Australia to win the world title on Boxing Day (as Johnson had done in 2008), but its plot was based on a plot line bought from a young, virtually unknown Sinclair Lewis (one of twenty-seven plotlines he bought from Lewis that year for a total of $137.50; The Dress Suit Pugilist cost $7.50). The novella had been rejected by more established and literary magazines (perhaps an indictment on its subject matter), but Popular Magazine, which specialised in adventure pulp paid $1,200 for it, twice the average annual wage at the time. It was published in novella form two years later. It is the last of London’s fictional works to focus on boxing, although the sport is referred to elsewhere in his writings several times. It was made into a Hollywood film twice. In 1923, a silent movie directed by Hobart Henley and starring Reginald Denny, Mabel Julienne Scott, Charles K. French and Hayden Stevenson; and in 1936, Conflict, a low budget film starring John Wayne and Jean Rogers.

The Abysmal Brute was published first in Popular Magazine in 1911 and was written in October 1910; it was published in book form in 1913 by the Century Company. It was influenced greatly by his coverage of the Johnson-Jeffries fight that had taken place on 4th July in Reno. Pat Glendon was based on Jack Johnson: Glendon’s walk was “smooth and catlike.” And Glendon had pursued Tom Harrison to Australia to win the world title on Boxing Day (as Johnson had done in 2008), but its plot was based on a plot line bought from a young, virtually unknown Sinclair Lewis (one of twenty-seven plotlines he bought from Lewis that year for a total of $137.50; The Dress Suit Pugilist cost $7.50). The novella had been rejected by more established and literary magazines (perhaps an indictment on its subject matter), but Popular Magazine, which specialised in adventure pulp paid $1,200 for it, twice the average annual wage at the time. It was published in novella form two years later. It is the last of London’s fictional works to focus on boxing, although the sport is referred to elsewhere in his writings several times. It was made into a Hollywood film twice. In 1923, a silent movie directed by Hobart Henley and starring Reginald Denny, Mabel Julienne Scott, Charles K. French and Hayden Stevenson; and in 1936, Conflict, a low budget film starring John Wayne and Jean Rogers.

Jack London’s delinquency at school had developed into bar room brawls later in life. He was consistently pugnacious, as were many others from his background. Recreational rumpus was a method of relaxation, particularly at times of stress. When a daughter died several days after she was born in 1910, London sought refuge in a bar brawl with an Irish saloon manager; both spent the night in jail, accusing each other of assault, though neither were charged. This fracas was one night before London was to travel to Reno to cover the Johnson and Jim Jeffries fight; one local newspaper wag commented wryly that London had wanted to be Jack Johnson’s challenger “if Jeffries takes the count.” But its formal counterpoint – sparring in the gym – had started when London was twenty years old. He had learnt to box when a member of the Socialist Labor Party, in Oakland in 1896; a fellow member, Herman ‘Jim’ Whitaker, had taught him, and he frequented the gym for most of his life thereafter. He befriended boxers, the great champion Bob Fitzsimmons and Jimmy Britt in particular. Although only 5 foot 7 inches tall, he was proud of his physique when younger and expressed general interest in physical fitness; his later ill health and torpor distressed him. He equated boxing with ruddy health and fitness. When returning from Australia on his boat, recuperating from pellagra, sparring on deck was his means of “getting into condition.” He told a reported in an interview of 1911, that of “all the games, it is the only one I really like.”

Jack London’s delinquency at school had developed into bar room brawls later in life. He was consistently pugnacious, as were many others from his background. Recreational rumpus was a method of relaxation, particularly at times of stress. When a daughter died several days after she was born in 1910, London sought refuge in a bar brawl with an Irish saloon manager; both spent the night in jail, accusing each other of assault, though neither were charged. This fracas was one night before London was to travel to Reno to cover the Johnson and Jim Jeffries fight; one local newspaper wag commented wryly that London had wanted to be Jack Johnson’s challenger “if Jeffries takes the count.” But its formal counterpoint – sparring in the gym – had started when London was twenty years old. He had learnt to box when a member of the Socialist Labor Party, in Oakland in 1896; a fellow member, Herman ‘Jim’ Whitaker, had taught him, and he frequented the gym for most of his life thereafter. He befriended boxers, the great champion Bob Fitzsimmons and Jimmy Britt in particular. Although only 5 foot 7 inches tall, he was proud of his physique when younger and expressed general interest in physical fitness; his later ill health and torpor distressed him. He equated boxing with ruddy health and fitness. When returning from Australia on his boat, recuperating from pellagra, sparring on deck was his means of “getting into condition.” He told a reported in an interview of 1911, that of “all the games, it is the only one I really like.” The Game, London’s first boxing novella, was written in 1905. It had started life as a short story. George P. Brett, London’s editor at Macmillan Co., enthusiastically recommended a series of such boxing tales. London preferred to develop the love story between Joe and Genevieve, and it took shape as a novella. It was published first in two issues of Metropolitan Magazine in April and May, and in four issues of The Tatler in Britain. Macmillan published in June, 1905, a revised version with additions, illustrated by Henry Hutt and T. C. Lawrence. Over 26,000 copies were registered for the first printing, and it was reprinted later that year in September. Reviews were generally favourable, although sales were not anywhere approaching those for The Call of the Wild and The Sea-Wolf from the previous two years. This book allegedly persuaded world champion Gene Tunney to retire from boxing in 1928.

The Game, London’s first boxing novella, was written in 1905. It had started life as a short story. George P. Brett, London’s editor at Macmillan Co., enthusiastically recommended a series of such boxing tales. London preferred to develop the love story between Joe and Genevieve, and it took shape as a novella. It was published first in two issues of Metropolitan Magazine in April and May, and in four issues of The Tatler in Britain. Macmillan published in June, 1905, a revised version with additions, illustrated by Henry Hutt and T. C. Lawrence. Over 26,000 copies were registered for the first printing, and it was reprinted later that year in September. Reviews were generally favourable, although sales were not anywhere approaching those for The Call of the Wild and The Sea-Wolf from the previous two years. This book allegedly persuaded world champion Gene Tunney to retire from boxing in 1928. The Abysmal Brute was published first in Popular Magazine in 1911 and was written in October 1910; it was published in book form in 1913 by the Century Company. It was influenced greatly by his coverage of the Johnson-Jeffries fight that had taken place on 4th July in Reno. Pat Glendon was based on Jack Johnson: Glendon’s walk was “smooth and catlike.” And Glendon had pursued Tom Harrison to Australia to win the world title on Boxing Day (as Johnson had done in 2008), but its plot was based on a plot line bought from a young, virtually unknown Sinclair Lewis (one of twenty-seven plotlines he bought from Lewis that year for a total of $137.50; The Dress Suit Pugilist cost $7.50). The novella had been rejected by more established and literary magazines (perhaps an indictment on its subject matter), but Popular Magazine, which specialised in adventure pulp paid $1,200 for it, twice the average annual wage at the time. It was published in novella form two years later. It is the last of London’s fictional works to focus on boxing, although the sport is referred to elsewhere in his writings several times. It was made into a Hollywood film twice. In 1923, a silent movie directed by Hobart Henley and starring Reginald Denny, Mabel Julienne Scott, Charles K. French and Hayden Stevenson; and in 1936, Conflict, a low budget film starring John Wayne and Jean Rogers.

The Abysmal Brute was published first in Popular Magazine in 1911 and was written in October 1910; it was published in book form in 1913 by the Century Company. It was influenced greatly by his coverage of the Johnson-Jeffries fight that had taken place on 4th July in Reno. Pat Glendon was based on Jack Johnson: Glendon’s walk was “smooth and catlike.” And Glendon had pursued Tom Harrison to Australia to win the world title on Boxing Day (as Johnson had done in 2008), but its plot was based on a plot line bought from a young, virtually unknown Sinclair Lewis (one of twenty-seven plotlines he bought from Lewis that year for a total of $137.50; The Dress Suit Pugilist cost $7.50). The novella had been rejected by more established and literary magazines (perhaps an indictment on its subject matter), but Popular Magazine, which specialised in adventure pulp paid $1,200 for it, twice the average annual wage at the time. It was published in novella form two years later. It is the last of London’s fictional works to focus on boxing, although the sport is referred to elsewhere in his writings several times. It was made into a Hollywood film twice. In 1923, a silent movie directed by Hobart Henley and starring Reginald Denny, Mabel Julienne Scott, Charles K. French and Hayden Stevenson; and in 1936, Conflict, a low budget film starring John Wayne and Jean Rogers.