Biography

SARAH ORNE JEWETT (1849 – 1909) set many of her stories in the fictional towns of Deephaven and Dunnet Landing; Dunnet Landing is clearly modelled on South Berwick, Jewett’s birthplace. These stories are sympathetic portraits of life in this locality – the small seaports and inland terrain of the southern sea coast of Maine – tell of its hardships and isolation, and avoid any sentimentality or histrionics. Jewett’s family were longstanding residents of New England and well-regarded; her father was a doctor and a keen amateur naturalist.

SARAH ORNE JEWETT (1849 – 1909) set many of her stories in the fictional towns of Deephaven and Dunnet Landing; Dunnet Landing is clearly modelled on South Berwick, Jewett’s birthplace. These stories are sympathetic portraits of life in this locality – the small seaports and inland terrain of the southern sea coast of Maine – tell of its hardships and isolation, and avoid any sentimentality or histrionics. Jewett’s family were longstanding residents of New England and well-regarded; her father was a doctor and a keen amateur naturalist.

As a child Jewett suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, and her treatment included going for lengthy walks or accompanying her father on his rounds of the fishing and farming communities of the area. Memories of this perambulatory ritual made their way into her writing. Much of Jewett’s writing is autobiographical and incorporates much of her childhood experience of the area, her love of its countryside and of thenatural world in general.

Jewett’s intellectual background was artisan and at ease with rural America. Her parental home had an impressive library, and she read widely as a child. She developed an interest in nonconformist religious ideas and had even joined the Episcopal Church in her early twenties; she was influenced greatly by the Swedish theologian and scientist Emanuel Swedenborg.

Jewett’s father died in 1878. From 1881 she lived sporadically in Boston but travelled in Europe for lengthy periods of time; but Maine remained the place where she felt most at home. Jewett never married. She shared a house most of her adult life with the writer Annie Adams Fields, the widow of James T. Fields, the publisher and editor of The Atlantic Monthly. Such domestic arrangement was common at this time and was referred to often as a Boston Marriage; there is no evidence that the two were lovers.

Sarah Orne Jewett’s first short story was published in 1869 when she was nineteen. Her first book, Deephaven, was published in 1877. Jewett’s writing thereafter was reviewed widely and favourably; William Dean Howells declared that she possessed “an uncommon feeling for talk – I hear your people.” An early successful novel was A Country Doctor (1884); a volume of short stories, A White Heron (1886), was well received and became her most anthologized story. As well as short fiction, Jewett wrote poetry and three children’s books. Some of her stories were translated by Thérèse Bentzon into French. Her last published work, The Tory Lover (1901) was not received well by critics but was her bestselling book. This suggests that her career had trajectory when it was cut suddenly short, for in 1902 Jewett sustained serious injury whilst travelling in a carriage. After this accident she suffered from forgetfulness and found concentration mostly impossible; she was able to write “nothing of consequence” in herlastyears. She had several strokes and died in June 1909.

Many critics have suggested that Jewett was not suited to longer literary form, that she was at her best composing sequences of related shorter stories. The Country of the Pointed Firs is indeed such a patchwork of parallel tales, stitched together yet often only casually incidental, bleeding into each other and bound tentatively as a novel. A sequence of storylines evolves with no dramatic arc or even of resolution; their format can be seen perhaps as a model for today’s TV soap operas. If her books include notable characters, then none are crucial to the story; rather these characters are foils to chronicle the world in which they move, and serve as ornaments to the panoramic social landscape of the narrative. It would have been no accident that Jewett’s writing desk was placed on the second floor of the family home and faced the Central Square in South Berwick. From there she could gaze at the random pedestrian recital of her town’s life, a panoramic view not dissimilar to that found in her fiction. The main setting of The Country of the Pointed Firs is the long street that runs through Dunnet Landing.

If The Country of the Pointed Firs has a main character, then it is Dunnet Landing itself. At the very beginning of the text, Jewett writes that to really know a village “is like becoming acquainted with a single person.” The book in many ways can be seen as a forerunner of Edgar Lee Masters’ poetry collection The Spoon River Anthology or of Sherwood Anderson’s modernist masterpiece Winnesburg, Ohio. Both authors took their childhood towns as their imaginative starting point. Coincidentally James Joyce had in 1905 begun to submit to publishers the early drafts of Dubliners, a literary psychogeography akin to Jewett’s.

Many significant contemporary writers and critics championed The Country of the Pointed Firs; Henry James considered it to be a “beautiful little quantum of achievement.” Willa Cather, who read Jewett keenly and met her eventually in 1908, thought this book to be a masterpiece. Jewett became Cather’s inspirational mentor, albeit briefly before her death the next year. Cather dedicated O Pioneers! to Jewett and went on to edit Jewett’s work in the 1920s.

Sarah Orne Jewett is presented as a leading light in the development of American local color writing – a literary category often used carelessly or with slight disparagement, sometimes even to denote nostalgia or quaintness. Her books may offer a sharp contrast to the emerging American literary themes of her day – urbanisation and industrialisation, railroads and migration – but all these social movements may be sensed in the hinterland of her writing. But if Jewett acknowledged the demands and momentum of the modern world and the effects it had on far-flung communities such as Berwick, Maine, then she was also a faithful witness to the continuation of social community. If New England’s shipping industry was struggling or its more marginalised agriculture faltering, then their adaptions to the prevailing economic trends need not disturb any link to its past or its tradition. The continuation of community is a main constituent of Jewett’s writing.

The Country of the Pointed Firs was published in November 1896 by Houghton, Mifflin and Company. It had been revised significantly and expanded by the author since its first outing earlier that year (in four issues of The Atlantic Monthly). Jewett included two more stories – Along Shore and A Backward Glance – in the 1896 edition, and two stories had been combined and lengthened to form The Bowden Reunion. Jewett went on to write a further three stories that were set in Dunnet Landing; a fourth was found unfinished upon her death. The completed stories were added by the publisher to the original text in reprints of 1910 and 1919, and had been encouraged to do so by Jewett’s sister. It has been argued that the book can be seen as an evolving piece of literature, a quality denied perhaps to the structure and narrative of a standard novel.

The Country of the Pointed Firs was published in November 1896 by Houghton, Mifflin and Company. It had been revised significantly and expanded by the author since its first outing earlier that year (in four issues of The Atlantic Monthly). Jewett included two more stories – Along Shore and A Backward Glance – in the 1896 edition, and two stories had been combined and lengthened to form The Bowden Reunion. Jewett went on to write a further three stories that were set in Dunnet Landing; a fourth was found unfinished upon her death. The completed stories were added by the publisher to the original text in reprints of 1910 and 1919, and had been encouraged to do so by Jewett’s sister. It has been argued that the book can be seen as an evolving piece of literature, a quality denied perhaps to the structure and narrative of a standard novel.

There are, then, various, competing editions of the text. Most subsequent editions have tended to follow the order of sequence determined by Willa Cather for the book’s 1925 edition, which included these additional stories. However there is no evidence that Jewett herself had blessed any of these inclusions; it is also possible that Jewett had loose plans to assemble a sequel to The Country of the Pointed Firs. It can be argued also that the expanded text upsets the balance of the original (by overly concentrating on the character of William). For these reasons, the additional three stories have been omitted from this edition.

She became also a designer of book covers, and from about 1884 until her death she designed over 220 books. She was a principal designer for Houghton Mifflin; Oliver Wendell Holmes and Celia Thaxter were, apart from Sarah One Jewett, perhaps the best known authors she designed for. She struck up a firm friendship with Sarah Orne Jewett that lasted until she died, and they corresponded tirelessly. Jewett welcomed Whitman’s critique and approval of her work. Jewett dedicated one volume of short stories, Strangers and Wayfarers (1890), to her. Fifteen of Jewett’s books have covers designed by Sarah Whitman.

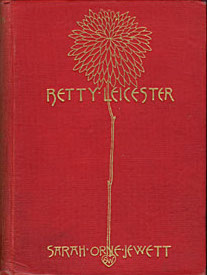

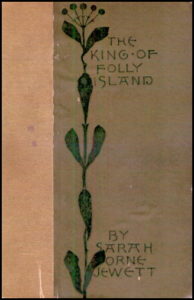

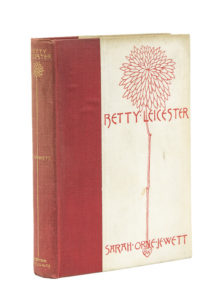

She became also a designer of book covers, and from about 1884 until her death she designed over 220 books. She was a principal designer for Houghton Mifflin; Oliver Wendell Holmes and Celia Thaxter were, apart from Sarah One Jewett, perhaps the best known authors she designed for. She struck up a firm friendship with Sarah Orne Jewett that lasted until she died, and they corresponded tirelessly. Jewett welcomed Whitman’s critique and approval of her work. Jewett dedicated one volume of short stories, Strangers and Wayfarers (1890), to her. Fifteen of Jewett’s books have covers designed by Sarah Whitman. Whitman’s book covers, influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau, were essentially minimalist. She helped herald a more artistically self-conscious element of simplicity to book presentation in America. Her colour of choice for a binding was green, of all shades, and she used usually one other colour for the design, often a gold or deep red. She used linear drawing and silhouette to great effect, often asymmetrical; flower or plant emblems were employed frequently, including often her own ‘flaming heart’ motif.

Whitman’s book covers, influenced by the Arts and Crafts Movement and Art Nouveau, were essentially minimalist. She helped herald a more artistically self-conscious element of simplicity to book presentation in America. Her colour of choice for a binding was green, of all shades, and she used usually one other colour for the design, often a gold or deep red. She used linear drawing and silhouette to great effect, often asymmetrical; flower or plant emblems were employed frequently, including often her own ‘flaming heart’ motif. “But will you please give directions at the Press that the old bindings should be restored to Betty Leicester? –the scarlet and white- for it is an ugly book at present; the die does not sit well sideways on the corner and this green and red cloth are very far from the beauty of Mrs. Whitman’s charming design.”

“But will you please give directions at the Press that the old bindings should be restored to Betty Leicester? –the scarlet and white- for it is an ugly book at present; the die does not sit well sideways on the corner and this green and red cloth are very far from the beauty of Mrs. Whitman’s charming design.”