Biography

The reputation of MARY ROBERTS RINEHART (1876 – 1958) may have stalled or even been traduced to parody since her death – she is referred to most often as the American Agatha Christie. Her writing has been mostly out of print in recent years; only her most famous book, The Circular Staircase, endures, perhaps as a tired classic. She was undoubtedly a trailblazer within the crime genre, and she was supremely commercial before all else (similar to Christie). But if popular in her day, Roberts Rinehart now is regarded as having more than one foot in the age in which she was born. In the decade after the Civil War had ended, her contemporary counterparts were the Victorians. The Circular Staircase, of course, comfortably predates the heyday of noir or hard-boiled crime writing. This is a restricted view of Rinehart.

Although she courted success, Rinehart’s career unfolded by accidental design rather than by accident. She wrote romance and comedy as well as mystery (rather like Christie), and her writing developed as much through a sense of personal fulfilment as through dictates of the market. Rinehart defined her own career and was mistress of it at all times. Greatness was not thrust upon her: she assembled it rather like the clues in her mystery books. She had written as a child (three short stories had been published by local newspapers for $1 each when she was fifteen), and turned to the craft as a business proposition when twenty-seven, certainly as a means to escape the gynaecological ailments that afflicted after she had given birth to three children, and to add colour to her life, but more for fiscal self-help She kickstarted her career only after she had discovered her husband’s financial frailty. He was a medical doctor – she had met him in Pittsburgh after her training as a nurse and had married in 1896 – who had played the stock market carelessly and landed his young family into difficulty in 1903, leaving them $12,000 in debt. Her husband could only make more house calls, but her response was to write short stories – she produced 45 in her first year – and serialized novels for the magazines, mostly for Munsey’s Magazine. This was a “magazine of the people and for the people” that had tried hard to dumb down  its content in the decades before Rinehart contributed. The Circular Staircase was the second of these novels, written in five instalments beginning in November 1907 for Munsey’s pulp specialist All-Story, which published Rex Stout and Edgar Rice Burroughs as well; it was transcribed into book form in 1908 with Bobbs-Merrill. Her second book, The Man in Lower Ten, which actually predated The Circular Staircase in its magazine completion, became the first mystery bestseller in America when published in 1909: it was the fourth ranked book of that year, and hit the public nail so hard that it was reported to have frustrated railroad porters when customers refused to sleep in carriage ten of overnight sleepers, the place of the book’s murder. Both these books feature Miss Cornelia van Gorder.

its content in the decades before Rinehart contributed. The Circular Staircase was the second of these novels, written in five instalments beginning in November 1907 for Munsey’s pulp specialist All-Story, which published Rex Stout and Edgar Rice Burroughs as well; it was transcribed into book form in 1908 with Bobbs-Merrill. Her second book, The Man in Lower Ten, which actually predated The Circular Staircase in its magazine completion, became the first mystery bestseller in America when published in 1909: it was the fourth ranked book of that year, and hit the public nail so hard that it was reported to have frustrated railroad porters when customers refused to sleep in carriage ten of overnight sleepers, the place of the book’s murder. Both these books feature Miss Cornelia van Gorder.

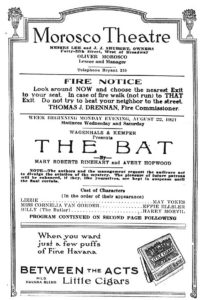

That there was an economic impulse to her writing can be seen in its rapid diversification. She was able to exploit the emerging leisured market and its many medium. In 1929 she even funded two of her sons with their publishing venture, Farrar & Rinehart, which became the vehicle for Rinehart’s new work. She started to write romance, comedy, even a Broadway farce in 1909: When A Man Marries was based on one of her novels, Seven Days. She wrote and produced nine plays throughout her career. The Bat, based on The Circular Staircase but with an arch-criminal called The Bat who  terrorized and left his bat symbol wherever he had perpetrated a crime (at one point a spotlight throws the image of the bat upon a wall, which inspired Bob Kane’s Batman iconography), ran successfully for 878 performances in New York; six additional companies staged the show elsewhere. She and her husband had invested much money in the production and reaped a significant return. The play’s novelization was in fact licensed (because of copyright issues with its film producers), ghost-written by Stephen Vincent Benet and published in 1926; its reincarnation on disc made it one of the first talking books, released in 1933 by RCA Victor. Many of her books migrated to film: The Circular Staircase four times, K and Miss Pinkerton, twice each. Even in her early years as a published author, she was in discussion over film rights. A friend was Beatrice DeMille, who tried to broker a deal for the book with her son, Cecil B. DeMille, but the rights to The Circular Staircase were sold eventually to Selig Polyscope Co. for a paltry amount, filmed first by Edward le Saint in 1915 to poor review; Essanay Studios had bought several short stories from her in 1914. Rinehart was perhaps too early for television, although some adaptions of her stories were screened in the 1950s.

terrorized and left his bat symbol wherever he had perpetrated a crime (at one point a spotlight throws the image of the bat upon a wall, which inspired Bob Kane’s Batman iconography), ran successfully for 878 performances in New York; six additional companies staged the show elsewhere. She and her husband had invested much money in the production and reaped a significant return. The play’s novelization was in fact licensed (because of copyright issues with its film producers), ghost-written by Stephen Vincent Benet and published in 1926; its reincarnation on disc made it one of the first talking books, released in 1933 by RCA Victor. Many of her books migrated to film: The Circular Staircase four times, K and Miss Pinkerton, twice each. Even in her early years as a published author, she was in discussion over film rights. A friend was Beatrice DeMille, who tried to broker a deal for the book with her son, Cecil B. DeMille, but the rights to The Circular Staircase were sold eventually to Selig Polyscope Co. for a paltry amount, filmed first by Edward le Saint in 1915 to poor review; Essanay Studios had bought several short stories from her in 1914. Rinehart was perhaps too early for television, although some adaptions of her stories were screened in the 1950s.

Very quickly Mary Roberts Rinehart’s career migrated from the mystery and comedy genre to writing unashamed potboilers. When she resumed her flood of mystery tales from the 1930s, it was with a more contemporary feel; some commentators have even attached the sentiment of hard-boiled fiction to her work and allied her with writers like Chandler and Hammett. But Rinehart has always been dismissed as lowbrow and too popular; critics like Howard Haycraft, the founding father of mystery criticism, derided her last two decades’ work, although he included The Circular Staircase in his “definitive library of mystery fiction” in his Haycraft-Queen Cornerstones bibliography of 1941. Rinehart’s husband encouraged her always to improve her literary worth.

Rinehart wrote hundreds of short stories in her career, produced a novel each year as well as books of travel and reportage; an autobiography, My Story, was published in 1931 and revised in 1948. She was prolific and was an instinctive writer, yet she had no training and had no literary friendships. In a letter to fan, September 29, 1945, she wrote: “What I really had was the ability to tell a story.” A staggering 4,000 words or more each day was her normal pace. She complained that her thoughts ran away with her and that she was not able to write fast enough to keep up with the speed of her thoughts. (Parker Pen Co., eager to exploit this product placement opportunity, created a special right-handed, snub-nosed fountain pen for her; it was described as having a “bold sweep,” and she became devoted to it.) To look at the bestseller lists for each year is revealing. Her books are rarely included in their annual top ten, which might indicate that she boasted a dedicated and loyal audience, and had a healthy reliance on reprint. It is alleged that cumulatively she was the highest paid author in America between 1900 and 1950. Upon her death in 1958 she had sold over 10 million volumes; The Circular Staircase alone accounted for well over a million of those.

Her writing might usefully be seen in the context of her personal life. Her parents’ domesticity rested on frail economics. Her father owned a sewing machine factory in Pittsburgh and was a thwarted inventor. The summit of his achievement had been to patent a rotary shuttle for sewing machines; his ambition was never realised, noted his daughter, and he fell back often to being a salesman on the road. Handsome, winsome and a hopeless dreamer, he committed suicide when Mary was nineteen (her uncle subsidised her education from this point). Her mother was a dressmaker who worked long hours, anxious it seems to keep up appearances of financial vigour. When money came to Mary later in her life, her response was to spend it. It need not be unlikely that such a tense financial background was the cause. One of Rinehart’s expensive habits was to purchase ruined houses that needed expensive restoration. The first house she bought from her earnings was at Glen Osborne, Pennsylvania and it required considerable overhaul: “all week long I wrote wildly to meet the payroll and contractor costs,” she wrote in her autobiography. She lived for a period in Washington, DC before relocating to New York in 1935, where she had a well-appointed 18-room apartment on Park Avenue. She had also a 24-room home in Bar Harbor, Maine.

There is throughout her life a sense of a delayed and displaced teenage revolt. That she detested overtly many of her adolescent duties – much housework was required of her as her mother took in two boarders, she disliked intensely her piano lessons – reads as little more than teenage huff. Of more interest is that she was left-handed by nature, and parental intervention meant that as a child she had her left hand tied behind her back often as correction. Any residual adolescent bitterness was softened by antidote in later life. As an adult delinquent she delighted to take her breakfast in bed; she smoked heavily. And there were huge streaks of non-conformity within her. The light-hearted Tish was introduced first in 1910 for upmarket literary magazines, and the first book, The Amazing Adventures of Letitia Carberry, was published a year later; Rinehart continued the character for twenty-seven years more, extended eventually to a further four volumes. She was in many, perhaps, Rinehart’s literary alter ego; certainly, some of the milder plot lines are exaggerated traces of her own experience. Tish, with her friends Aggie and Lizzie, pursued the almost impossible for women of her time: she raced motor cars, hunted for shark and wild bear, and drove ambulances in France during the First World War; she was a sort of Yankee and female Biggles. Rinehart in her own life indulged a sense of danger and adventure; even with a background of family duty, she pursued wilderness vacations, committed defiant acts of independence, participated in outdoor and field sports. She was fearless during the First World War: The Saturday Evening Post, upon her instruction, produced for her letters of introduction that gave access to the Belgian front line, where she was the first female war correspondent. Rinehart managed to interview not only Churchill and the Queen of Belgium but also Queen Mary; also she was in Paris when the armistice was signed. (The earliest of her war time exploit made readable reportage in Kings, Queens, and Pawns: An American Woman at the Front, 1915). Rinehart was, too, an intrepid traveller: she defied death as she navigated the Cascades on horseback via a seldom explored pass, and she crossed uncharted rapids on the Flathead River in a precarious wooden boat. One of the essays in her book The Out Trail (1923) is called Roughing It with the Men. Nomad’s Land (1926) is an account of her 100-mile trek on a camel through Egypt; her attitude is very much to hike up her skirt and get on with it.

Her stance on social issues was hardly timid. She marched as a suffragette. She was an advocate for Native American rights and was initiated into the Blackfoot Tribe. She tackled issues not often in the public domain of her time. She wrote of domestic violence, well before such an issue was spoken of in public. (Her own marriage was not happy, and her husband, who died in 1932, was resentful of her success.) She spoke of her mastectomy and advocated for breast examination; she announced her fight with breast cancer in an interview that was published in the Ladies’ Home Journal, 1947. “To all of us,” ran the cover feature, “she says: Face Your Danger In Time.”

Her stance on social issues was hardly timid. She marched as a suffragette. She was an advocate for Native American rights and was initiated into the Blackfoot Tribe. She tackled issues not often in the public domain of her time. She wrote of domestic violence, well before such an issue was spoken of in public. (Her own marriage was not happy, and her husband, who died in 1932, was resentful of her success.) She spoke of her mastectomy and advocated for breast examination; she announced her fight with breast cancer in an interview that was published in the Ladies’ Home Journal, 1947. “To all of us,” ran the cover feature, “she says: Face Your Danger In Time.”

The Circular Staircase was the first example of the Had-I-But-Known school of writing. Always the  narrator misses all clues of impending disaster, and all is revealed at the plot’s conclusion. This is a style that tires if not done well; Ogden Nash parodied it with his poem Don’t Guess Let Me Tell You, and Rinehart was wise to move on with her plotting techniques. It was assumed readily that the John F. Singer House on the east side of Pittsburgh was the book’s setting, a rich man’s vanity project from 1869, expensively furnished, marbled, and deserted when Rinehart wrote her novel; its swirling staircase was one of the building’s pretentious calling cards. Rinehart revealed that the book had been inspired by her visit to Melrose, a Gothic Revival castle with a three-storey-octagonal tower in Northern Virginia.

narrator misses all clues of impending disaster, and all is revealed at the plot’s conclusion. This is a style that tires if not done well; Ogden Nash parodied it with his poem Don’t Guess Let Me Tell You, and Rinehart was wise to move on with her plotting techniques. It was assumed readily that the John F. Singer House on the east side of Pittsburgh was the book’s setting, a rich man’s vanity project from 1869, expensively furnished, marbled, and deserted when Rinehart wrote her novel; its swirling staircase was one of the building’s pretentious calling cards. Rinehart revealed that the book had been inspired by her visit to Melrose, a Gothic Revival castle with a three-storey-octagonal tower in Northern Virginia.

Rachel Innes, a dowager easily persuaded by her niece and nephew, rents a country house for the summer. On the second night there, the owner’s son is found dead at the bottom of the staircase; others disappear and a sequence of crime and foreboding unravel; evidence isn’t shared with the inert Detective Jameson; amateur sleuth Rachel stumbles into a sequence of crimes, often in danger; all is revealed in the end.

There is a stiff backbone of reality to Rinehart’s writing that is not present with her Anglican rival, Agatha Christie. Rinehart was more socially alert and wrote about all levels of society with compassion; if a revolver was found in the shrubbery, then the shrubbery needn’t have contained roses; there is soot and sweat aboard her railroad train. There is a touch of authenticity that alluded Christie. Even in their respective real time criminal dramas, Rinehart wins. Christie staged her own suicide in 1926 when she drove her car to a quarry’s edge and vanished for ten days; newspaper hullabaloo was resolved when she was found in a Harrogate hotel registered in the name of her husband’s mistress. Rinehart’s cataclysm was in 1947 whilst at her home in Maine. Her servant for twenty-five years fired a gun at her and attempted to carve her up with a knife; she was rescued by her other servants and the attacker killed himself in his prison cell the next day. “The butler did it” is a phrase ascribed to Rinehart, supposedly taken from The Door, a lacklustre novel of 1930, but in her life the butler really did it. Unlike Christie’s implausible tableaux and faux testimony, things really did happened in the fiction of Mary Roberts Rinehart, too.