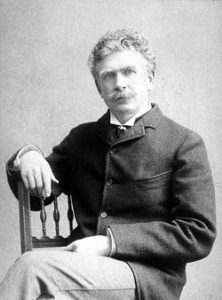

Biography

Bierce was a leading light of realist fiction, a short story writer of renown who wrote often of the American Civil War; he embraced horror and satire too. His most anthologised story is An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (an early example of the stream of consciousness narrative); Kurt Vonnegut hailed it to be the greatest American short story ever written. The Devil’s Dictionary is loved and much quoted by its disciples even today. He was a prolific and influential journalist, and his literary criticism was held in high regard when he was alive. Yet if his name is mentioned today, it might be more for historic observance than for literary currency. If he is considered still to be a noteworthy notch in America’s literary history, he is no longer read or enjoyed as before.

Bierce was a leading light of realist fiction, a short story writer of renown who wrote often of the American Civil War; he embraced horror and satire too. His most anthologised story is An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (an early example of the stream of consciousness narrative); Kurt Vonnegut hailed it to be the greatest American short story ever written. The Devil’s Dictionary is loved and much quoted by its disciples even today. He was a prolific and influential journalist, and his literary criticism was held in high regard when he was alive. Yet if his name is mentioned today, it might be more for historic observance than for literary currency. If he is considered still to be a noteworthy notch in America’s literary history, he is no longer read or enjoyed as before.

AMBROSE BIERCE was born in a log cabin in Ohio in 1842. (His twelve siblings were each given a Christian name also beginning with the letter ‘A’.) His forebears were of English descent, having arrived on American soil in the early seventeenth century as part of the Great Puritan Migration. Bierce railed against suggestions of any inheritance of “Puritan values” from his family; he was an avowed agnostic, for sure, but he was scornful often of his genealogy or those who were interested in it, and certainly scornful of anybody who tried to relate his family’s values to Bierce’s personality. He did, however, inherit from his parents a love of books and reading. When 15 he became a ‘printer’s devil’, an apprentice in the print workshop of a small, abolitionist newspaper in Ohio. In 1861 he enlisted in the Union Army’s 9th Indiana Regiment, and this act can be seen to be the crux of his life.

Bierce had an energetic Civil War. Almost immediately he received public acclaim for his bravery when newspapers reported that he had rescued a wounded soldier while under fire (who subsequently died). He took part in one of the fiercest of the war’s battles at Shiloh in 1862, an experience that shook him greatly. What I Saw of Shiloh, included in this volume, is an effective piece of retrospective reportage that is graphic and devastatingly woebegone, and not marked with the sardonic humour that is the trademark of his fictional writing. His discovery of a forest fire that had incinerated immobile, injured soldiers is particularly harrowing. He came across one sergeant still alive, even though he had been shot in the head, “taking in his breath in convulsive, rattling snorts, and blowing it out in sputters of froth which crawled creamily down his cheeks;” his “brain protruded in bosses, dropping off in flakes and strings.” One of Bierce’s men, “a womanish fellow,” suggested he run a bayonet through the suffering soldier, but Bierce was too discomposed by both the image and the suggestion. “I told him I thought not,” wrote Bierce; “it was unusual, and too many were looking.”

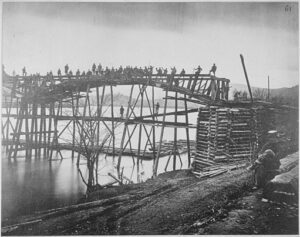

Regular advancement up the military ranks followed, and by early 1863 he was appointed to be a ‘topographical engineer’ (a mapmaker); this is undoubtedly why Bierce’s stories are flooded with such detail of the landscape. The lull from the bloodshed this post afforded prompted serious and cynical reflection. “Whole squadrons of cavalry escort sometimes,” he wrote, “had to be sent thundering against a powerful infantry outpost in order that the brief time between the charge and the inevitable retreat might be utilized in sounding a ford or determining the point of intersection of two roads.” Nevertheless, he re-enlisted at the end of 1863.

Bierce received a severe head injury on Kennesaw Mountain in June, 1864. He had been shot by a sharpshooter, and was found on the battlefield by his brother, Albert. He did return to the war After his recovery but resigned from duty in early 1865, though not discharged until a few months later. The effects of this injury – fainting fits and extreme irritability – were to disturb him for the rest of his life.

The battlefield catastrophe he had witnessed first-hand served as the basis for several of his short stories. Killed at Resaca and Chickamauga (a battle in which he participated) are notable examples. H. L. Mencken mischievously described Mark Twain, William Dean Howells and Henry James as “draft-dodgers,” and it is remarkable that many of the military stories of the late nineteenth century were written by those who spent no time fighting. Bierce was one of the few significant Civil War writers who had campaigned as a soldier (others included John W. DeForest, Sidney Lanier and Theodore Winthrop); critics at the time agreed that Bierce’s portrayal of war was more accurate than Stephen Crane’s, his popular rival. Indeed, it is certainly his experience of the battlefield that makes his realistic writing a harbinger of Hemingway’s rugged and intimate depiction of fighting.

The most interesting of Bierce’s short stories were written between 1889 and 1891 in a three year burst of creative energy. They are at their best when concerning warfare. At one time in my green and salad days,” he wrote nearly four decades later. “I was sufficiently zealous for Freedom to engage in a four years’ battle for its promotion:” Bierce’s depiction of war is neither elegiac nor heroic. He never mythologized war, just as he never exalted heroism, and if he portrays an individual as heroic, then it is a perversion of what the popular writing of his time declared this to be. In his writing heroism is portrayed usually as hopeless or paradoxical, and is often conflated with the fear of death. There is always a large dose of savage humour or parody, which helps reveal a true sense of the waste and pointlessness of warfare. There is also profound absurdity in the actions of his central characters. Carter Druse in A Horseman in the Sky is forced to shoot his own father. Captain Coulter in The Affair at Coulter’s Notch follows orders to shell his own house, thereby killing his family. In A Son of the Gods, an officer rides in advance to draw the Confederate fire and save his men, but his men, “choking with emotion,” are all killed when they lunge forward to avenge his death. The soldier’s true enemy is rarely the opposing rank of soldiers, rather it is the terror of the pain and death they can inflict that has more bite. Those who cannot confront this fear are characters he depicts well. Captain Graffenreid in One Officer, One Man is unable to conquer his fear of battle and commits suicide; but it transpires it is only a light skirmish that lies ahead. Jerome Searing in One of the Missing dies of fright, his rifle pointed to his head when in a collapsed building; it is revealed later that his rifle was not even loaded.

Bierce wrote many ghost stories also. Some have suggested that he was a forerunner of the psychological horror story. H. P. Lovecraft, on whom he was a great influence, described Bierce’s writing as “grim and savage.” Much else of his writing would now seem to fit the varied genre of ‘weird fiction’ (Lovecraft’s analysis), and it would have been interesting to see how his writing might have progressed had he been exposed to the twentieth century pulp magazine. He emphasised consistently the absurd and improbable, and at times can be charged with being overtly disrespectful of considered literary form. Maupassant was an obvious influence on his use of “trick endings.”

For most of his lifetime, Bierce was known foremost for his journalism and not his fiction, though it appears he stumbled into journalism with little planning. He spent time after the Civil War as a Treasury agent which this was tedious and short-lived. He was then involved in an attempt to map the Overland Trail westward, a futile project. This landed him in San Francisco where his first job, as a nightwatchman in a mint, proved to be so dull that he turned to writing in 1867. He served a disparate apprenticeship, which included a stay in London between 1872 and 1875 (where he published his first books). His rise as a journalist, interrupted by a short spell working as a manager for a mining company, was inexorable, though he rarely took on stories away from a Californian interest. By the 1880s he had his own weekly column called ‘Prattle’ in a San Franciscan magazine he was editing, The Wasp, and he began to work for William Randolph Hearst on the San Francisco Examiner. His writing, if parochial, was humorous and confrontational, at times controversial. These are ingredients that guaranteed a large and growing readership, and in a very short time he became a leading voice on the West Coast. His investigative writing was usually specifically honed, efficient and highly effective. He waged a successful war, for instance, upon the railroad refinancing bill in 1896, which was designed to excuse Union Pacific and Central Pacific from repaying their enormous government loans. He even ruined his boss’s run for Presidential office, in this instance inadvertently, when Hearst’s enemies wilfully misinterpreted a poem Bierce had written (Hearst incriminated as its publisher) by claiming that it had called for McKinley’s assassination in 1901.

AMBROSE BIERCE’S DEATH is shrouded in mystery. In December 1913 he embarked on a field trip to cover the Mexican Revolution, during which he disappeared without trace. He is known to have been suffering from severe asthma attacks and had not ridden a horse for some time before this journey; moreover he was seventy-one years of age. After a trip reminiscing through the Louisiana and Texas Civil War battlefields, Bierce passed through El Paso to Mexico where it is supposed that he joined rebel Pancho Villa’s army as an observer; there is evidence that he witnessed the Battle of Tierra Blanca. A last letter (now lost) dated 26th December, 1913, finished with the note: “As to me, I leave here tomorrow for an unknown destination,” though the destination is likely to have been Ojinaga where the Villistas were headed. Thereafter his fate is shrouded with inconclusive debate and unsubstantiated leads. The most dramatic speculation, affirmed by a local priest, is that he was shot by a firing squad in Sierra Mojada, Coahuila. (He had told Mencken earlier that year earlier of his plans to visit Mexico, where he might “incur the mischance of standing against a wall to be shot.”). It is more likely, however, that he was killed when Ojinaga was captured. Bierce’s death was the subject of much future writing; Carlos Fuente’s novel The Old Gringo is perhaps best known.

When William Dean Howells, the high-minded gendarme of late nineteenth century American literary life, asserted that Ambrose Bierce was “among our three greatest writers,” Bierce’s rapid-fire response was, “I am sure Mr. Howells is the other two.” In his writing and in his life, Ambrose Bierce was celebrated for his wit; Mencken no less referred to Bierce as “the one genuine wit that These States have ever seen.” But wit can hide a cavern of despair.

There is a circular quality to Bierce’s life. He was in denial of both his upbringing and his family. He was shaped more than anything else by his experience of warfare, and, in spite of its dubious complexities and irrationality, he found it difficult to make sense of life after. It is speculative, but it is almost as though he found life apart from wartime to have hollow purpose. His marriage had ended disastrously; his two sons had died before him, one from alcoholism, the other by suicide. By 1912, Bierce may not have had many reasons to keep him alive, especially after he had finished editing the twelve volumes of his Collected Works, a flattering project initiated by publisher Walter Neale, who was to complain of the derisive comments made by some critics (such as “potatoes set in platinum!”). That Ambrose Bierce died in another pointless civil war may have been tragically appropriate.

a military bridge on the Tennessee River 1863