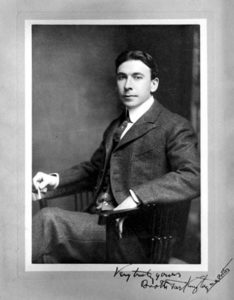

Biography

BOOTH TARKINGTON (1869-1942) had a huge readership and much acclaim during his lifetime. Literary Digest in 1922 declared him to be America’s greatest living author, and that same year The New York Times placed him on their list of the twelve greatest living Americans (he was the only writer included). Tarkington sold over five million copies of his books, a remarkable achievement in a pre-paperback age. Most of his novels made notches on the bestseller lists, and he was well rewarded with huge financial advances. Yet since his death he has never curried favour with critics or maintained a devoted readership. Publishers have served him poorly since, and today he merits only a single volume in the catch-all Library of America series (published in 2019).

Tarkington can hardly lay claim to be definitively redolent of his time, for his fiction was set often decades before its time of writing and it had a nostalgic gaze. Moreover, he is seen by many to have sat on the wrong side of history, and his reactionary politics may often have blinded those reading his work retrospectively to its merits. This may be unfair, for if he were writing today it is not unlikely that he would find a significant following among those who seek to invest in rootedness, locality and community, those who distrust technology and mistrust globalism, or those who reject the environmental costs of motor transport.

Tarkington’s first published book was The Gentleman from Indiana, published in 1899; his first successful book, Monsieur Beaucaire, which was actually written first, was published in 1900. His early writing – he had been supported financially since he had left Princeton by his uncle’s bequest – was overtly melodramatic and romantic; these qualities were toned down in his later fiction but were never eradicated. Politics emerged as a recurrent theme, especially after Tarkington’s own political career had come to an early end through ill-health. His uncle, Newton Booth (after whom he was named) had been governor of California, and Tarkington shared his family’s feelings of responsibility and duty. In 1902 he served for only one term in the Indiana house of Representatives, until he succumbed to a serious bout of typhoid. Tarkington’s first collection of short stories, In the Arena, published in 1905, had political themes. Roosevelt was impressed enough to invite him to the White House, where he berated the author for suggesting that political life was no “business for a gentleman,” but generally gave praise (“Of course, I just sat & purred,” wrote Tarkington). Roosevelt borrowed the book’s title for his now celebrated 1910 address, ‘Citizenship in a Republic’.

A sequence of books written during the first World War featured Penrod, an American forerunner of the mischief by happenchance character of Richmal Crompton’s William Brown (who similarly was written for an adult audience). Inspired perhaps by Tarkington’s three nephews, these highly successful books of stand-alone stories bound together as novels were hailed as children’s classics immediately and Tarkington’s reputation rivalled Mark Twain’s. The house his wife had built in Maine was referred to as “the house that Penrod built,” although Tarkington was by now earning serious money as a playwright too. The tone of these books is difficult to accept today and Tarkington is best remembered now for his more than thirty novels. The first novel to draw serious attention was The Turmoil (1915), which delineated a common theme to Tarkington’s writing – the effect of progress and greed upon a relentless businessman, James Sheridan, and his family. This theme was developed further in its sequel, the first of his Pulitzer prizewinning novels, The Magnificent Ambersons (1918).

Tarkington was to win the Pulitzer for a second time with Alice Adams (1921), a novel he described as “about as humorous as tuberculosis.” It is the finest of his novels without doubt, realistic and unsentimental, and with a finely drawn, self-aware heroine, capable of nuanced thinking; these virtues are not always present with Tarkington’s characters. Alice Adams can be seen as the highpoint of Tarkington’s literary career though rather than the point at which he finds his voice; his writing hereafter collapses into predictability, however well-paced and coherent.

The critical silence that Tarkington’s work merits today is in stark contrast to, say, F. Scott Fitzgerald, his later Princeton rival. Fitzgerald and many of his contemporaries, such as Nathanael West, were able to articulate so clearly in their writing disillusionment with the so-called American Dream, defined by James Truslow Adams in his book The Epic of America. Steinbeck, Sinclair Lewis and Tarkington’s fellow Hoosier, Theodore Dreiser, were exploring complex societal issues in a more dramatic and confrontational way. A whimsical regret at the destruction of America’s previous sober and rural aspect is what you get with Tarkington. It is easy to argue that the absence of the progressive thought and zeal of so many of his contemporaries suggests little bite to the drama of his novels, but his novels did offer still a satirical observation of America’s burgeoning class system, albeit restrained and presented at times in moral tone.

A focus on nostalgia is not the stuff of revolution, and, if placed alongside the socialists and high-minded progressivists of his day, Tarkington’s lack of dissent might make his societal commentary read as tepid, though an interesting corrective to the accepted worldview of embracing change as good and progressive. Rather, he sought to chronicle life in small-town America and delineate its transformation from the idyllic aspect of his imagination (and privilege) into a squalid mess of concrete, soot and toil. Even so, Tarkington was shrewd enough to see that progress was not of itself wrong. He did balk at an easy or unquestioning acceptance of progress. In his novels, those families who acquiesce and seek to benefit from the new world order are those who suffer the most; George Minafer, the grandson of Major Amberson, the family patriarch who dispenses ease and stability in The Magnificent Ambersons, is a spoiled young man who seeks to build new family fortunes on new technologies, especially the automobile trade, and he comes a cropper.

Even in the late 1920s Tarkington – who favoured prohibition and went on to oppose FDR’s New Deal in the 1930s – could describe himself as “the liberal of a former age.” That he was a reactionary above all else can be seen in his much-cited disapproval of the motor car. And his disapproval was not based necessarily on the social upheaval caused by the “horseless carriage,” or the exploitation of the labour force used to support it; rather it is the aesthetic asperity that the motor car introduced. An early centre of the motor trade was Indiana: “No one could have dreamed that our town was to be utterly destroyed,” he wrote in his autobiography. Ultimately Tarkington comes across as somebody who did not accept or like progress regardless of its consequence; he was, to his detractors, the supreme antiquarian and lacking curiosity. Similarly, that Tarkington was not interested in literary modernism goes without saying. His reactionary opinions on art, also, were dropped into his novels like too much salt in a soup. Art was one of his great interests; he occasionally illustrated his own books and was a serious collector; as a trustee of the Indianapolis art institute he worked hard to keep Picasso out of its collection.

That Tarkington found himself to be at ease in American society of his youth can hardly be surprising. His family had remained financially comfortable and politically well-connected even after the Panic of 1873 had shed much of its wealth. His beliefs and attitudes were informed by this privileged childhood and adolescence for sure; ill-health aside – he had a heart attack in 1912, suffered from alcoholism until then but cured himself (“I preferred to die sober”), he became increasingly blind from 1920 and wrote eventually using an amanuensis – his later life was marked by contentment and achievement; he had an innate sense of self-preservation and propriety that served as defence against excess of any kind, even as a young man. To claim, as his critics do, that Tarkington’s background can explain the weaknesses in his writing may be a red herring. He is not the only artist not to have suffered for his art, and not the only social observer to lament the move away from the world order that favoured him. A lack of enquiry enough to successfully imagine or inhabit the lives of those dissimilar to his or a tendency to rest in his own comfort are damning observations of a writer who in the 1920s was considered to be America’s greatest, but it may indicate only that his writing was overrated in his lifetime, and that public taste can be accounted for not only by matters less solemn than is sometimes wished. Carl van Doren was always sceptical of Tarkington’s literary reputation: even in 1921 he wrote that “whenever he comes to a crisis in the building of a plot or in the truthful representation of a character he sags down to the level of Indiana sentimentality.” But what we do find in Tarkington still is a shrewd eye for the psychology of relationships (if slightly inclined to generalise) and a lament for lost ways. He can be celebrated too for the Midwest setting of his writing.

CONTENTS

Great Men’s Sons

A Boy and His Dog

The Party

The One-hundred Dollar Bill

Willamilla